Building Rural Power: Midwest CROP Workshop Brings Legislators and Partners Together

Building Rural Power: Midwest CROP Workshop Brings Legislators and Partners Together

By Siena Chrisman

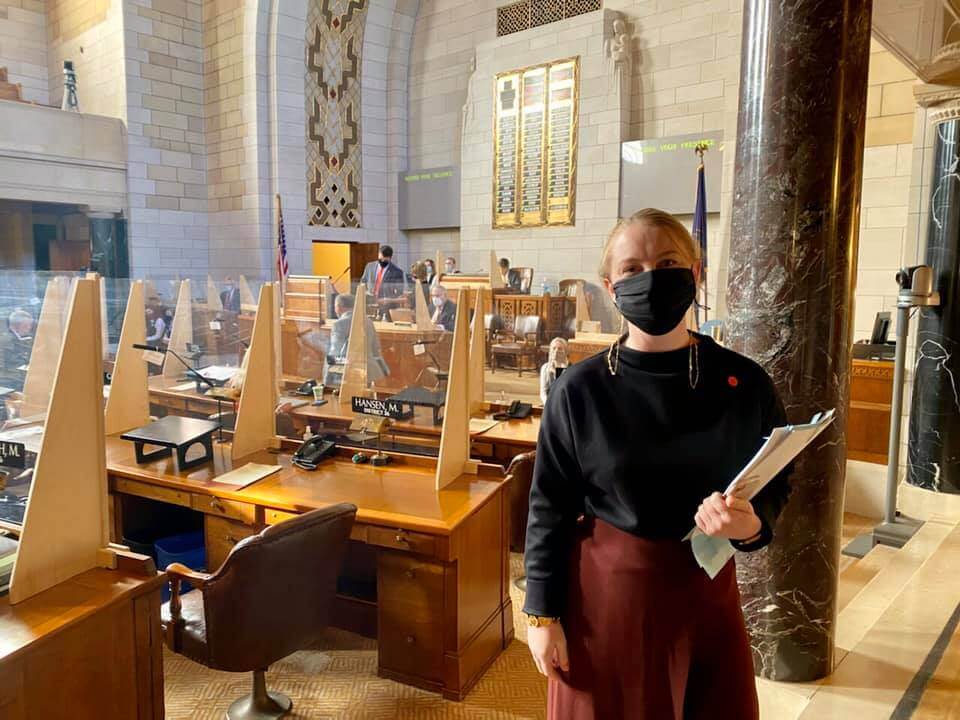

At the end of June, SiX hosted its first Midwest Movement-Building Convening and Farm Tour, in and around Omaha, Nebraska. Ten state legislators from six Midwestern and Plains states joined SiX staff, our partners at Nebraska Communities United, and other regional rural advocates for two days of tours, learning, and strategy sessions.

The event was part of SiX’s ongoing investment in progressive organizing across perceived urban/rural divides. While urban and rural communities are often painted as diametrically opposed, the reality is that Americans face common struggles and share common values no matter where they live. Bringing together urban and rural leaders to build relationships and learn about each others’ realities is a critical way to build progressive power for the future we want.

After setting the stage with a short Nebraska agriculture history, analysis of corporate power, and research on rural values, the group spent a day on the ground in rural Nebraska, seeing both some of the worst extractive industrial agriculture practices and inspiring, scalable regenerative farms.

Greg Lanc, a farmer and farm machinery mechanic, took the group on a tour of his rural neighborhood, which has been overrun by dozens of concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs): large-scale chicken barns, a cattle feedlot, an enormous calf-feeding operation, a mega dairy, and more. A CAFO of one kind or another is visible from nearly every intersection of the gravel roads in a several-mile radius of Lanc’s house.

The chicken houses, where millions of Costco’s $4.99 rotisserie chickens are raised, are the worst, spouting dust, bacteria, and an overpowering smell of ammonia into the surrounding air. Many days, Lanc cannot spend time outside on his property because the smell is so bad. Chicken and feed trucks kick up dust and wear down the gravel roads and Lanc has documented dead chickens left in open dumpsters just uphill from streams. Costco promised the barns and the nearby chicken processing plant would bring jobs and other economic benefits to the community, but that has not been the case.

This kind of factory-style farming is often touted as an economic boon for rural communities, but research repeatedly proves what the neighbors know: industrial farms extract far more than they add. There are, however, numerous models of beneficial farm operations, including nearby in Nebraska.

Legislators and partners had lunch and a tour of Grain Place Foods, a regenerative farm and grain business. The farm has been certified organic in 1978 and its fields go through a nine-year rotation of grains and pasture for cattle, building healthy soil and a thriving ecosystem. The grains are processed at an on-site mill and sold in products locally, around the country and the world. Between the farm and the mill, Grain Place employs about two dozen workers, many of whom have worked there for decades, ensuring that the business not only invests in its natural resources, but in the economic health of its community.

Low clouds had threatened rain all day, but by the time the tour reached its last stop at Alex Daake’s farm, the sun was shining through. Daake has recently taken over part of his family’s land and is in the process of transitioning to a four-year rotation of corn, soybeans, small grain, and pasture. He grazes cattle on the pasture and sells them for beef. Between keeping a lookout for the newest calf born just that morning and admiring the many grasses, forbs, legumes, and flowers growing in the pasture, legislators discussed ways that state policy and other initiatives could support more diversified farm operations like this one.

On the final morning, back in Omaha and absorbing all they had experienced the day before, legislators heard about bridge-building organizing in Nebraska, Louisiana, Illinois, North Carolina, and elsewhere. They had stories of unexpected coalitions creating David-over-Goliath victories, like a mostly-red rural Oregon community partnering with progressive Portland legislators to pass rules to protect communities from new CAFOs; rural and urban Minnesota activists and legislators building long-term trust and determining priorities for a progressive policy agenda for the state, and much more.

Legislators and advocates left the convening excited to keep talking, to visit each other, and to dream across state lines. They went back to their districts with a greater sense of possibility for who their allies and partners might be – one urban legislator, considering previous stereotypes and all the people he had met over the two days, said, “I learned that I’m not as alone as I thought I was.”