Reimagining Public Safety: Resources for State Action

Introduction

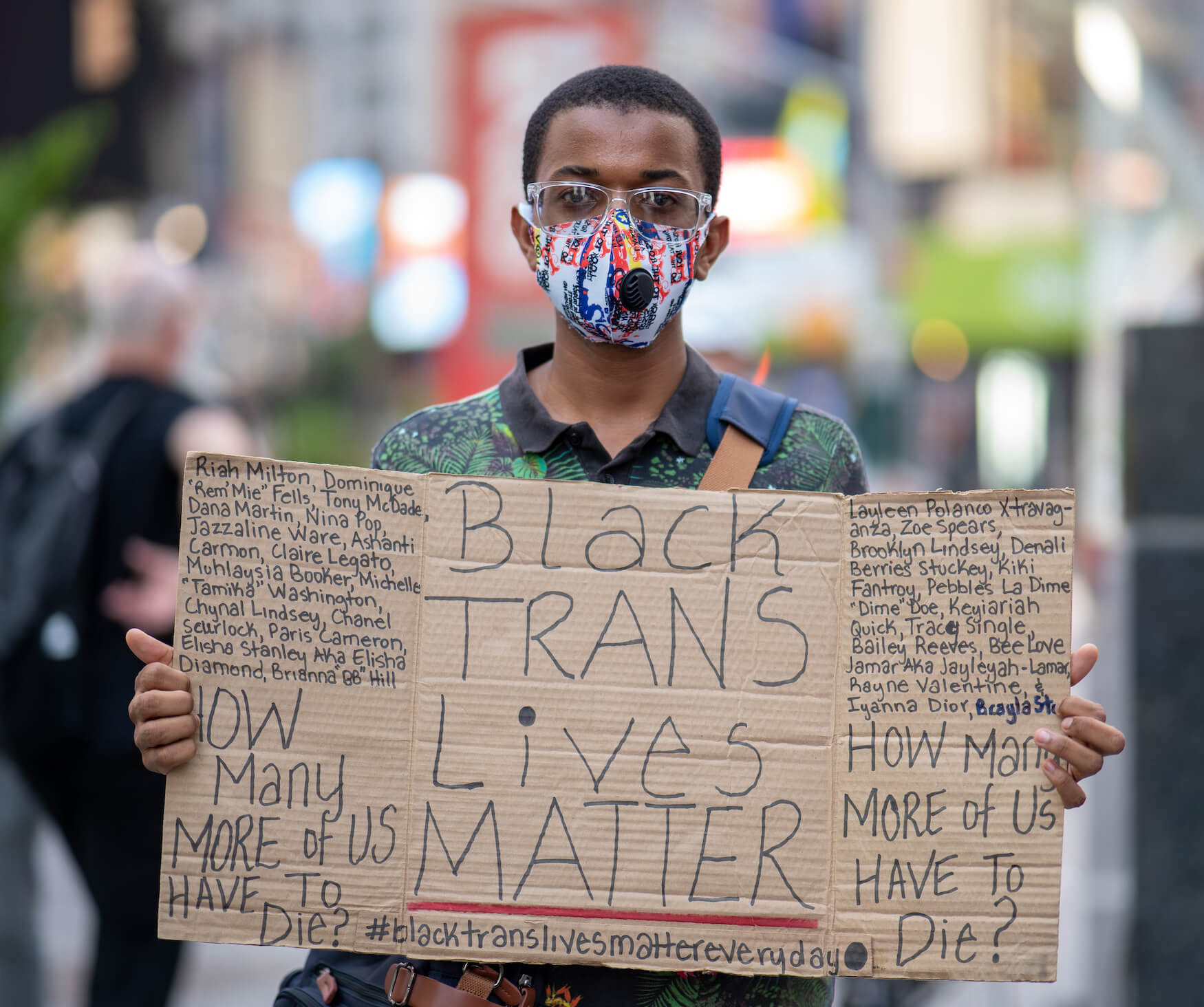

When a jury found Derek Chauvin guilty on all charges in the murder of George Floyd, accountability was, at last, applied to a police officer. But we must not let this single trial lessen the urgency of demands for changes to the violent system of policing in this country. Accountability does not equate to justice. Justice would be George Floyd alive today, living in a world that knows the Black lives matter. Justice would be an end to the constant, unrelenting police violence that takes the lives of nearly 1,000 Americans each year and terrorizes the lives of thousands more.

Incremental policy changes haven’t stopped the killings and one guilty verdict will not, either. We need to reimagine public safety in America. Each murder of yet another Black person by the police shows we need to transform our approach to public safety. In the words of the Movement for Black Lives, “There is no ‘reforming’ this system—the time is now to divest from deadly policing and invest in a vision of public safety that protects us all.”

SiX compiled the resources below following the guilty verdict in the trial of Officer Derek Chauvin, who killed George Floyd in May 2020. Read our full statement here.

Enacted Legislation

The police don’t keep everyone safe. We need a new approach to public safety that truly protects everyone from harm. Since the murder of George Floyd, 30 states have passed more than 140 new laws related to public safety, but we know from the continued murders and violence inflicted on Black and brown people that this is not enough.

As you consider the introduction of public safety legislation, we encourage you to reach out to your legislative peers in these states who have sponsored this legislation. These leaders carry a depth of knowledge about the policy, and can also talk to you about their strategies, the obstacles, what didn’t make it into the legislation (and why), and what they’re working on next (SiX can help connect you). We need to learn lessons from state to state, rather than copying and pasting a one-size-fits all approach, so we can collectively accelerate our work toward justice where all people feel safe in their communities.

“The only way to diminish police violence is to reduce contact between the public and the police.” — Mariame Kamba

Changes to oversight, accountability, training, and police policies are essential for harm reduction, but to truly transform public safety into a system that works for all, alternatives to policing must be pursued. For starters, mental health, traffic, gender-based violence, and crime investigation services could be better fulfilled by other trained, unarmed, and nonviolent professionals. The list of legislation below is not comprehensive.

Structural Reforms

Activists and communities have been calling for fundamental changes to policing for many years. The more recent “Defund the Police” campaigns envision a new system that goes beyond incremental police reforms. As The Opportunity Agenda puts it in Beyond Policing:

What would it look like to have first responders who were unarmed mental health specialists work with those experiencing a crisis in public? How would it be different for those experiencing homelessness if they had an ongoing relationship with a trained social worker instead of periodic encounters with police?

While we are unaware of any state to make fundamental changes to the notion of policing in America, the Beyond Policing report highlights local examples of restorative justice, peacemaking circles, mobile crisis centers, youth and community courts, stipends and other supports for individuals at-risk of perpetrating violence.

The following legislative examples are small steps that states have taken to move away from a model of policing and punishment to one that provides true safety for all members of the community, including alternatives to policing, a halt on automatic police department funding supports, and de-militarization of police departments.

Alternatives to Policing

Enacted legislation in Connecticut (2020 CT HB 6004) requires the Connecticut Department of Emergency Services and Public Protection and local police departments to evaluate the feasibility and potential impact of using social workers to respond to calls for assistance or accompany a police officer on certain calls for assistance.

Colorado enacted legislation (2020 CO HB 1393) expanding the state’s Mental Health Diversion Pilot Programs from four to five or more in selected judicial districts that identifies individuals with mental health conditions who have been charged with a low-level criminal offense and divert such individuals out of the criminal justice system and into community treatment programs.

Police Department Budgets

Colorado legislation (2020 CO HB 1375) repealed the State Division of Criminal Justice's authority to spend unused appropriations for the Law Enforcement Assistance Grant Program in the following year. Local law enforcement agencies, which include county and municipal agencies and district attorneys, therefore have access to less grant funding in FY 2020-21, and potentially in future years.

De-Militarization of Police

California (2020 CA SB 480) enacted legislation prohibiting a law enforcement agency from authorizing or allowing its employees to wear a uniform that is made from a camouflage printed or patterned material or a uniform that is substantially similar to a uniform of the United States Armed Forces or state active militia.

Comprehensive policing reform legislation in Connecticut (2020 CT HB 6004) prohibits law enforcement agencies from acquiring certain “1033 program” military equipment; requires police departments to submit an inventory report to the legislature; and it allows the executive branch to require law enforcement agencies to sell, transfer, or dispose of equipment found to be unnecessary for public protection.

The D.C. Council enacted a bill (2020 DC B23-0825) to prohibit District law enforcement agencies from acquiring “ammunition of .50 caliber or higher; armed or armored craft or vehicles; bayonets; explosives or pyrotechnics, including grenades; firearm mufflers or silences; firearms of .50 caliber or higher; firearms, firearm accessories, or other objects, designed or capable of launching explosives or pyrotechnics, including grenade launchers; and remotely piloted, powered aircraft without a crew aboard, including drones” from any federal government program. Under the new law, District agencies are also required to relinquish any such property within 180 days after the effective date of the law.

A bill (2021 IL HB 3653) passed by Illinois lawmakers prohibits the State Police from requesting or receiving tracked armored vehicles; weaponized aircraft, vessels, or vehicles; firearms of .50 caliber or higher; ammunition of .50 caliber or higher; grenade launchers; or bayonets.

Virginia lawmakers enacted legislation (2020 VA SB 5030) to prohibit the acquisition of certain weapons and equipment from the Department of Defense, including weaponized unmanned aerial vehicles, combat aircraft, surplus grenades and grenade launchers, surplus armored vehicles, bayonets, firearms of .50 caliber or higher, ammunition of .50 caliber or higher, and weaponized tracked armored vehicles.

Limiting Police Engagement

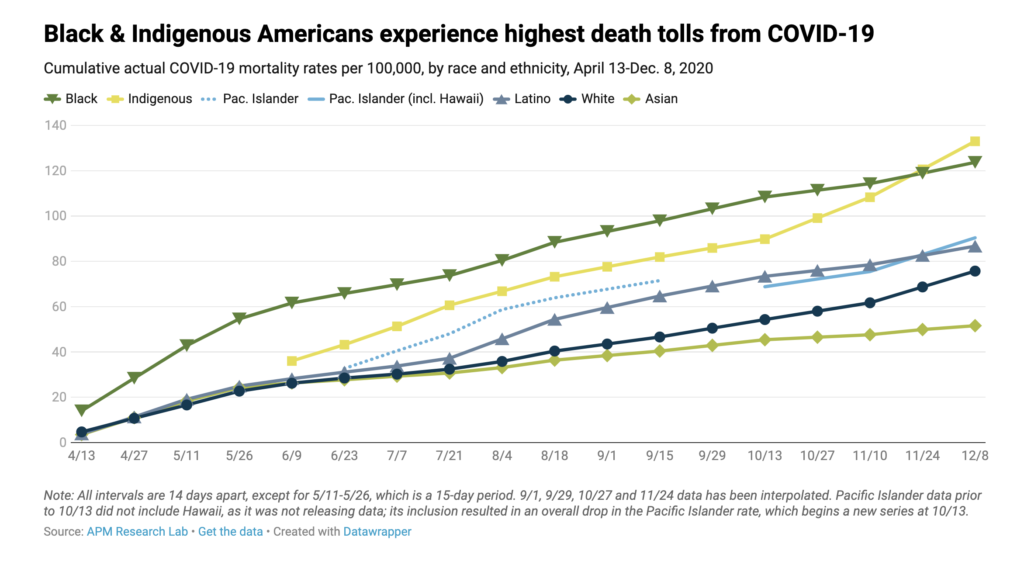

Police involved violence disproportionately impacts Black and brown communities. Mapping Police Violence provides powerful data showing that:

- Black people were 28% of those killed by police in 2020 despite being only 13% of the population.

- Black people are 3 times more likely to be killed by the police than white people, and 1.3 times more likely to be unarmed when killed by the police.

- Most killings by police begin with traffic stops, mental health checks, domestic disturbances, or reported low level offenses.

To reduce violence during police interactions, states have enacted legislation to reduce over policing, regulate the use of “no-knock” search warrants, limit the use of deadly force, ban chokeholds, require police officers to intervene to stop excessive use of force or to render medical aid, and train police officers in topics from de-escalation to implicit bias.

Use of Force and Chokehold Bans

Legislation enacted in California (2019 CA AB 392) specifies that a police officer is only justified in using deadly force to defend against an imminent threat of death or serious bodily injury to the officer or to another person or to apprehend a fleeing person who the officer reasonably believes will cause death or serious bodily injury to another person unless immediately apprehended. The law prohibits a police officer from using deadly force against someone who only poses a danger to themselves.

California legislation (2019 CA AB 1196) prohibits a law enforcement agency from authorizing the use of a carotid restraint hold or a choke hold. The California law defines “carotid restraint” as a vascular neck restraint or any similar restraint, hold, or other defensive tactic in which pressure is applied to the sides of a person's neck that involves a substantial risk of restricting blood flow and may render the person unconscious in order to subdue or control the person. And “choke hold” is defined as any defensive tactic or force option in which direct pressure is applied to a person's trachea or windpipe.

A comprehensive police reform bill enacted in Colorado (2020 CO SB 217) creates a new use of force standard by limiting the use of physical force and limiting the use of deadly force when force is authorized. The act prohibits a peace officer from using a chokehold.

Enacted legislation in Connecticut (2020 CT HB 6004) limits the circumstances under which a law enforcement officer’s use of deadly physical force is justified and establishes factors to consider when evaluating whether the actions were reasonable. The law also limits an officer’s use of a chokehold or similar restraints.

Delaware state legislators enacted 2020 DE HB 350 which creates a new felony charge called “aggravated strangulation.” This charge is reserved for acting law enforcement officers who knowingly or intentionally use a chokehold on a person. This law creates an exception for officers who deem the use of force necessary to save the life of another law enforcement officer. The law does not limit the state from pursuing further charges to the officer beyond the aggravated strangulation charge.

The D.C. Council enacted a comprehensive package of policing reforms (2020 DC B23-0825) that included a ban on the use of neck restraints by law enforcement officers as a form of lethal and excessive force. The legislation also established new requirements for the “reasonable” use of force, which includes a consideration of the use of de-escalation measures and “whether any conduct by the officer prior to the use of deadly force increased the risk of a confrontation resulting in deadly force being used.”

Illinois recently enacted criminal justice reform legislation (2021 IL HB 3653) that includes statewide standards on use of force, crowd control responses, de-escalation, and arrest techniques. It also broadens the prohibition on using a chokehold to also include any restraint above the shoulders with risk of asphyxiation, unless the use of deadly force is justified.

Police reform legislation in Indiana (2021 IN HB 1006) defines “chokehold” as a use of deadly force and prohibits the use of a chokehold under certain circumstances.

Legislation enacted in Iowa (2020 IA HF 2647) states that the use of a chokehold is only justified when the person being arrested has used or threatened to use deadly force in committing a felony, or when the police officer reasonably believes the person would use deadly force against any person unless immediately apprehended. The new law defines “chokehold” as the intentional and prolonged application of force to the throat or windpipe that prevents or hinders breathing or reduces the intake of air.

Recently enacted legislation in Maryland (2021 MD SB 71) that requires a police officer to take steps to de-escalate conflict without using physical force, and prohibits a police officer from using force that is not necessary and proportional to prevent imminent physical injury or to effectuate a legitimate law enforcement objective. The law specifies that this use of force must cease after the suspect is under the police officer’s control, no longer poses an imminent threat, or after it is determined that force will no longer accomplish a legitimate law enforcement objective.

Legislation in Massachusetts (2020 MA SB 2963) identifies the general circumstances under which police officers can use physical force, and specifically bans the use of chokeholds and prohibits firing into a fleeing vehicle unless doing so is both necessary to prevent imminent harm and proportionate to that risk of harm. The bill also generally precludes officers from using rubber pellets, chemical weapons, or canine units against a crowd. Violations of any of these provisions may provide grounds for an officer to have their certification suspended or revoked.

Legislation enacted in Minnesota (2020 MN HF 1) makes changes to the state’s use of force laws, including limiting the authority of police officers to use deadly force unless based on a specific threat likely to occur absent action by the officer, and one that requires the officer to address it through the use of deadly force without unreasonable delay. This law also provides that an officer must be able to articulate the threat with specificity and restricts the use of deadly force in cases where the person only presents a danger to themself.

Nevada lawmakers enacted legislation (2020 NV AB 3) to prohibit the use of chokeholds by law enforcement officers on another person or placing a person who is in custody of a law enforcement officer in any position that restricts their ability to breathe. The bill also amends existing statute to clarify that “only the amount of reasonable force necessary to effect the arrest” may be used if a defendant flees or forcibly resists, whereas previous law provided for the use of “all necessary means.”

New Hampshire lawmakers (2020 NH HB 1645) enacted legislation to prohibit the use of chokeholds by law enforcement officers, except to defend themself or a third person from imminent deadly force.

Lawmakers in New York approved the “Eric Garner Anti-Chokehold Act” (2019 NY S 6670/A 6144), which creates a new class C felony offense for “aggravated strangulation.” Under the new law, law enforcement officers who obstruct breathing or blood circulation or use a chokehold, as is prohibited under existing law, and cause serious physical injury or death to another person is guilty of aggravated strangulation.

Oregon legislators enacted a bill (2020 OR HB 4203) to ban the use of chokeholds unless deadly physical force is otherwise allowed under the law. The bill also directs the state Board on Public Safety Standards and Training to adopt new rules for police and reserve officer training requirements that reflect the new prohibition of the use of chokeholds.

Later in the year, Oregon lawmakers passed another bill (2020 OR HB 4301) updating the recently-enacted chokehold ban to include corrections officers and removing the exception on the use of chokeholds in circumstances where use of deadly force is allowable. Under the new law, officers must give a verbal warning, allow time for compliance, and use of de-escalation tactics before physical and deadly uses of force.

Legislators in Utah passed a bill (2020 UT HB 5007) to prohibit the use of chokeholds, defined as “the application of a knee applying pressure to the neck or throat of a person” by peace officers. The bill provides for a referral to the county or district attorney for review and to the state’s Peace Officer Standards and Training Council for investigation and classifies the prohibited restraint as a third-degree felony, a second-degree felony if it results in serious bodily injury or loss of consciousness, or a first-degree felony if it results in death. The bill further prohibits the inclusion of chokeholds in peace officer training curriculum approved by the state.

Utah lawmakers also enacted a bill (2021 UT SB 106) to require the state’s Peace Officer Standards and Training Council to establish minimum use of force standards. The new law also requires compliance with the use of force standards by peace officers and enforcement of the standards by law enforcement agencies.

Another bill (2021 UT HB 237) passed by the Utah legislature limits the proper use of deadly force to prevent death or serious bodily injury to the officer or an individual other than the suspect. Prior law authorized the use of deadly force in instances where someone posed a threat of death or serious bodily injury to themselves, in addition to the officer or others.

In Vermont, lawmakers passed a bill (2020 VT S 119) to set new standards for use of force by law enforcement. Under the new law, use of force must be “objectively reasonable, necessary, and proportionate” and “based on the totality of circumstances.” Another bill (2020 VT S 219) passed by legislators banned the use of chokeholds and amended the state’s existing code of unprofessional conduct of law enforcement officers to include the use of chokeholds and failing to intervene and report when observing another officer using a prohibited restraint or using excessive force.

Virginia legislators enacted a bill (2020 HB 5069) to define and prohibit the use of neck restraint by law enforcement officers, unless its use is “immediately necessary to protect the law-enforcement officer or another person.” The bill creates a new disciplinary penalty, in addition to existing penalties under the law, for the use of neck restraints, including dismissal, demotion, suspension, transfer, or decertification.

Legislators in Washington enacted a bill (2019 WA HB 1064) to narrow the state’s criminal statutes on the use of deadly force by law enforcement officers to an objective standard of good faith that “a similarly situated reasonable officer would have believed that the use of deadly force was necessary to prevent death or serious physical harm to the officer or another individual.” Previously, state statute also provided for use of deadly force under a subjective good faith test that the officer “intended to use deadly force for a lawful purpose and sincerely and in good faith believed that the use of deadly force was warranted in the circumstance,” in addition to an objective good faith test.

Duty to Intervene and Report Misconduct

Police reform legislation enacted in Colorado (2020 CO SB 217) requires a police officer to intervene when another officer is using unlawful physical force and requires the intervening officer to file a report regarding the incident. If a police officer fails to intervene when required, the police standards board is required to decertify the police officer.

Comprehensive policing reform legislation in Connecticut (2020 CT HB 6004) requires police and correction officers to intervene when fellow officers use unreasonable, excessive, or illegal force and to report on those incidents. This law also prohibits law enforcement units and the department of corrections from retaliating against an intervening and reporting officer.

Criminal justice reform legislation enacted in Illinois (2021 IL HB 3653) provides both a duty to intervene for police officers to prevent or stop another police officer from using unauthorized or excessive force, and also a duty to render medical aid and assistance, including performing CPR and getting an injured suspect to a hospital.

Kentucky enacted legislation (2021 KY SB 80) to include failure to intervene when it is clear that a fellow police officer is using unlawful and unjustified excessive or deadly force as a form of professional nonfeasance that can lead to termination and decertification as a police officer.

Maryland legislation (2021 MD SB 71) requires a police officer to intervene to prevent or terminate the use of force by another police officer that goes beyond what is authorized by law, and it requires an officer to render basic first aid to a person injured as a result of police action and promptly request appropriate medical assistance.

Massachusetts police reform legislation (2020 MA SB 2963) requires a police officer to intervene to prevent the use of unreasonable force and report the incident to an appropriate supervisor. The law also requires each law enforcement agency to develop procedures to report abuse by fellow police officers without fear of retaliation.

Legislation enacted in Minnesota (2020 MN HF 1) establishes a duty for police officers to intercede when another officer is using excessive force and report incidents of excessive force to supervisors. Failure of a police officer to intercede or report excessive force subjects the officer to police standards and training board discipline.

Nevada legislators enacted a bill (2020 NV AB 3) requiring any peace officer to monitor any person in their custody for signs of distress and to take actions to place them in a recovery position if necessary. The bill also requires any peace officer who uses physical force on another person to ensure that medical aid is rendered as soon as practicable. Finally, peace officers are required to prevent or stop another officer from using physical force that is not justified, and to report the incident to their immediate supervisor in writing within 10 days.

In New Hampshire, legislators enacted a bill (2020 NH HB 1645) to require law enforcement officers to report misconduct by other officers. Under the new law, officers must report the misconduct to the chief law enforcement officer in their department, or the Police Standards and Training Council if the chief officer is the subject of the report, in writing immediately, or as soon as practicable. The chief law enforcement officer must notify the Police Standards and Training Council of the misconduct in writing within 7 days. The bill further requires law enforcement departments to conduct an investigation of reports of misconduct in a timely manner.

In New York, lawmakers passed legislation (2019 NY S 6601/A 8226) to affirm the duty of law enforcement officers to provide medical and mental health attention to a person under arrest or otherwise in their custody. The bill further creates a civil cause of action for any person who has not received such medical attention and as a result, suffers serious physical injury or significant exacerbation of an injury or condition.

Oregon lawmakers enacted a bill (2020 OR HB 4205) to require police and reserve officers to intervene to prevent or stop another officer engaged in an act of misconduct, and to report such an act to a supervisor as soon as practicable, but no later than 72 hours after witnessing the misconduct. Under the new law, failure to intervene or report constitutes grounds for disciplinary action by the agency or grounds for suspension or revocation of the officer’s certification by the Department of Public Safety Standards and Training. Finally, the bill provides anti-retaliation protections to officers who intervene or report misconduct of another officer.

A bill (2020 VA HB 5029) passed in Virginia requires law enforcement officers to intervene when witnessing another officer engaging in or attempting to engage in the use of excessive force. Officers are also required to end the use of force or prevent its further use where feasible, to render aid to any person injured as a result of the use of excessive force, and to report the misconduct. Law enforcement officers who fail to comply with the new law are also subject to disciplinary action.

No-Knock Search Warrants

Legislation in Illinois (2021 IL HB 3653) was enacted to, among other things, require police departments to develop plans to protect children or other vulnerable people present during search warrant raids.

Recently enacted Kentucky legislation (2021 KY SB 4) prohibits the issuance of a no-knock arrest warrant unless for specific suspected violent offenders and, based on established facts, giving notice prior to entry will endanger the life or safety of an individual, or result in the loss or destruction of evidence. Another bill, “Breonna’s Law” (2021 KY HB 21), which was developed in response to the murder of Breonna Taylor during the execution of a no-knock warrant with input from community members failed to advance

In Maryland, lawmakers enacted a bill (2021 MD SB 178) over a gubernatorial veto that amends the process for the execution of search warrants and narrows the use of no-knock search warrants. Under the new law, unless exigent circumstances are determined to exist, no-knock search warrants shall only be executed between 8 am and 7 pm.

Comprehensive police reform legislation in Massachusetts (2020 MA SB 2963) places strict limits on the use of so-called “no-knock” warrants, requiring such warrants to be issued by a judge and only in situations where an officer’s safety would be at risk if they announced their presence and only where there are no children or adults over the age of 65 in the home. The legislation provides for an exception when those children or older adults are themselves at risk of harm.

Virginia lawmakers passed a bill (2020 VA HB 5099) banning no-knock search warrants. The bill also requires that warrants be executed in the daytime unless law enforcement can provide good cause for nighttime execution of warrants. Another bill (2021 VA SB 1475) passed by legislators clarifies that the ban applies to “any place of abode,” and that daytime hours are considered between 8 am to 5 pm.

Overpolicing

California enacted legislation (2020 CA AB 1215) prohibiting a law enforcement agency or officer from installing, activating, or using any biometric surveillance system in connection with or data collected by an officer camera. The law authorizes a person to bring an action for equitable or declaratory relief against an agency or officer who violates that prohibition. California also enacted legislation (2020 CA AB 1775) that increases the penalty for a violation if a person knowingly allows the use of or uses the 911 emergency system for the purpose of harassing another. The penalty increases if the act is defined to be a hate crime.

Comprehensive policing reform legislation in Connecticut (2020 CT HB 6004) makes a number of changes to limit the frequency or extent of police interactions with the public. The Connecticut law limits the circumstances under which law enforcement officials may conduct consent searches on (1) an individual’s body and (2) motor vehicles stopped solely for motor vehicle violations. This law also generally prohibits law enforcement from asking for non-driving identification or documentation for stops solely for motor vehicle violations. And the new law raises the penalties for false reporting crimes or misusing the emergency 9-1-1 system when committed with the specific intent to do so based on certain characteristics of the reported person or group (e.g. race, sex, or sexual orientation). Finally, it prohibits municipal police departments and the Connecticut Department of Emergency Services and Public Protection from imposing pedestrian citation quotas on their police officers.

A recently enacted bill in Illinois (2021 IL HB 3653) may reduce police traffic stops by eliminating license suspensions for unpaid fines and fees due to red light cameras and traffic offenses.

Legislation recently enacted in Maryland (2021 MD HB 670) requires that absent exigent circumstances, at the commencement of a traffic stop or other stop, a police officer must (1) display proper identification to the stopped individual and (2) provide specified identifying information regarding the officer and the reason for the traffic stop or other stop. A police officer may not prohibit or prevent a citizen from recording the police officer’s actions if the citizen is otherwise acting lawfully.

Enacted legislation in Massachusetts (2020 MA SB 2963) requires law enforcement to seek a court order when conducting a facial recognition search, except in emergency situations.

In June 2020, New York enacted legislation (2020 NY A 1531) which amended civil rights laws in the state to include reporting a non-emergency incident to police and emergency services involving a member of a protected class. This law charges civil penalties for frivolously calling the police in order to target a member of a protected class, if no imminent threat or danger is detected by the officer.

Police Training and Screening

California enacted legislation (2019 CA SB 230) that requires the commission on police officer standards and training to implement courses of instruction for the regular and periodic training of law enforcement officers on de-escalation, implicit and explicit bias and cultural competency, use of force scenario training, alternatives to use of deadly force and physical force, and using public service, including the rendering of first aid, to provide a positive point of contact with the community. Legislators also enacted 2020 CA AB 846 which required the Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training to study and update regulations and screening materials to identify explicitly and implicit biases against protected classes related to emotional and mental evaluations of officers. It also requires evaluations of peace officers to include evaluations of biases against protected classes. Lastly, it requires law enforcement to change job descriptions to deemphasize paramilitary aspects of the job and to place more emphasis on community interaction and collaboration.

Another bill passed in California (2020 CA AB 3099) would require the Department of Justice to provide technical assistance related to tribal issues to local law enforcement agencies and tribal governments with Indian lands. Such assistance includes guidance for law enforcement education and training on policing and criminal investigations on Indian lands. The bill also requires the department to conduct a study to determine how to increase state criminal justice protective and investigative resources for reporting and identifying missing Native Americans in California, particularly women and girls.

Police reform legislation enacted in Colorado (2020 CO SB 217) gives the police standards and training board the authority to revoke a police officer’s certification if the officer fails to complete a required training after being given 30 days notice to satisfactorily complete the missed training.

Enacted legislation in Connecticut (2020 CT HB 6004) adds implicit bias training to required police training components.

The D.C. Council passed legislation to change existing continuing education requirements for law enforcement officers to include “biased-based policing, racism, and white supremacy,” “obtaining voluntary, knowing, and intelligent consent from the subject of a search,” and the duty of an officer to report misconduct or excessive force by another officer.

Illinois recently enacted legislation (2021 IL HB 3653) to require police officer training on topics such as proper use of force techniques, de-escalation, implicit bias and racial and ethnic sensitivity.

Recently enacted legislation in Indiana (2021 IN HB 1006) requires the Indiana law enforcement training board to establish mandatory training in de-escalation as part of the use-of-force curriculum, and requires de-escalation training to be provided as a part of: (1) pre-basic training; (2) mandatory inservice training; and (3) the executive training program.

Legislation enacted in Iowa (2020 IA HF 2647) requires the Iowa Law Enforcement Academy (ILEA) Council in consultation with the Iowa Civil Rights Commission, advocacy organizations, and various interest groups and stakeholders, to develop, provide, and disseminate mandatory annual training to every law enforcement officer employed by a law enforcement agency on matters related to de-escalation techniques and the prevention of bias.

Recent Maryland legislation (2021 MD SB 71) requires police officers to undergo training on when an officer may or may not draw a firearm, point a firearm at a person, and the enforcement options that are less likely to cause death or serious physical injury, including de-escalation tactics. Related legislation (2021 MD HB 670) requires all law enforcement agencies to use implicit bias testing in the hiring process and requires all police officers to complete implicit bias testing and training annually.

Comprehensive legislation in Massachusetts (2020 MA SB 2963) provides for police training on de-escalation and disengagement, alternatives to use of force for children, community trust building, and cultural competency.

Minnesota legislation (2020 MN HF 1) prohibits the police officer standards and training board from approving “warrior-style” training and prohibits police chiefs from providing that training to their officers.

Nebraska state legislators recently enacted a law (2020 NE LB 924) which required law enforcement agencies to adopt racial profiling prevention policies. This law adds anti-bias and implicit bias training and testing to minimize racial profiling, and also requires law enforcement officers to record the race and ethnicity of people they stop. Lastly, the bill requires two hours of anti-bias and implicit bias training to the continual education requirements for law enforcement officers and sheriffs.

In Nevada, legislators enacted a bill (2019 NV AB 478) that updates existing continuing education requirements for peace officers to include no less than 12 hours in courses that address racial profiling, mental health, the well-being of officers, implicit bias recognition, de-escalation, human trafficking, and firearms.

Lawmakers in New Hampshire enacted a bill (2020 NH HB 1645) that redirects existing funds from the Drug Forfeiture Fund to reimburse local governments or the state for psychological stability screenings for law enforcement officer candidates.

Pennsylvania legislators unanimously approved a bill (2020 PA HB 1910) that updates mandatory training requirements for police officers to include training on trauma-informed care, use of deadly force, de-escalation and harm reduction techniques, community and cultural awareness, implicit bias, procedural justice, and reconciliation techniques. The bill also creates a new requirement for mental health evaluations and related treatment upon the request of an officer, the recommendation of their chief or supervising officer, or within 30 days of an incident of the use of lethal force.

State legislators in Utah enacted a bill (2021 UT HB 0162) to create new required training for law enforcement officers in mental health and crisis intervention responses, arrest control, and de-escalation tactics. This bill also requires annual reporting of training hours by department.

Incident Response

Investigations of police interactions that result in death or other serious incidents that are shrouded in secrecy, influenced by the offending police officer, and/or conducted by a biased entity degrade public trust in law enforcement agencies. Adequate levels of independence in any response to a critical incident caused by a law enforcement officer ensure that future measures of accountability honor the truth of what occurred.

State lawmakers can ensure that responses to serious incidents are independent and faithfully carry out justice under the law by increasing reporting requirements, protecting the right of witnesses to record incidents, preserving the integrity of available recordings, and requiring an independent investigation of incidents.

Reporting In-Custody Deaths or Incidents

Illinois legislators enacted sweeping criminal justice and police reforms with the passage of 2019 IL HB 3653, including new requirements for law enforcement agencies to increase transparency and accountability. The bill requires agencies to investigate and report incidents in which a person dies while in custody or as a result of an officer’s use of force to the state Criminal Justice Information Authority within 30 days of the death. Such reports shall be open to public inspection, and an annual report on in-custody deaths, disaggregated by race, gender, sexual orientation, and gender identity shall be published annually.

Legislation (2019 NY S 2575/A 10608) passed in New York creates a new reporting requirement for any law enforcement officer who discharges their weapon where a person could be struck by a bullet from the weapon. The officer is required to make a verbal report within 6 hours to their supervisor and file a written report within 48 hours of the incident.

A bill (2021 UT HB 264) passed in Utah creates new reporting requirements when law enforcement officers point a firearm at an individual or aim a “conductive energy device at an individual and displays the electrical current.” The officer is required to file a report with information about the incident within 48 hours to their agency.

Right to Record

In Nevada, lawmakers enacted a bill (2020 NV AB 3) that protects the right of any person not under arrest or in the custody of a peace officer to record law enforcement activity and to maintain custody and control of the recording and any instruments used to make the recording. The bill prohibits peace officers from interfering with such recordings or seizing the recording or instruments used to record.

New York legislators passed the “New Yorker’s Right to Monitor Act” (2019 NY S 3253/A 1360), which affirms the right of any person not under arrest or in the custody of law enforcement officials to record law enforcement activity and to maintain custody and control of the recording and any instrument used to make the recording. The legislation also creates a private right of action for any unlawful interference with recording a law enforcement activity.

Police Body Cameras and Dashboard Cameras

Beginning in July 2023, a comprehensive police reform bill enacted in Colorado (2020 CO SB 217) requires all police officers, with some exceptions, to wear and activate a body-worn camera when responding to a call for service or during any interaction with the public initiated by the peace officer when enforcing the law or investigating possible violations of the law.

Enacted legislation in Connecticut (2020 CT HB 6004) expands the requirement to use body cameras to police officers in all state, municipal, and tribal law enforcement units, and it requires these officers to use dashboard cameras in police patrol vehicles.

The D.C. Council enacted legislation (2020 DC B23-0825) to require the release of unredacted body-worn camera footage within 5 business days to the Council upon request. The Mayor is also required to publicly release the names and body-worn camera recordings of all officers involved in incidents of death or serious use of force, with input on a public release from the victim or decedent’s next of kin. Under the new law, officers are prohibited from viewing recordings to assist in initial report writing.

Recent legislation in Illinois (2021 IL HB 3653) requires the use of body-worn cameras by police departments statewide, with a phase-in from 2022 to 2025 depending on the size of the municipality and county.

A recently enacted bill in Indiana (2021 IN HB 1006) specifies that a law enforcement officer who turns off a body-worn camera with the intent to conceal a criminal act commits a Class A misdemeanor.

Legislation enacted in Maryland (2021 MD SB 71) provides that all law enforcement agencies must require the use of body-worn cameras by July 1, 2025, with the state police and a few selected counties starting two years earlier.

In New Mexico, the state legislature passed and enacted a bill (2020 NM SB 8) to require municipal, county, and state law enforcement officers to wear a body-worn camera while on duty. It also requires law enforcement agencies to establish policies and regulations around their use, such as requiring them to be on during public interactions or requiring videos to be retained by the agency for at least 120 days.

New York lawmakers passed a bill (2019 NY A 8674/S 8493) to require all state police officers to wear body-worn cameras at all times while on patrol. Under the new law, the cameras are required to record certain actions and interactions with the public. The bill also authorizes the attorney general to investigate instances where body cameras fail to record an event that is required to be recorded by the new law.

Independent Investigation of Deaths or Other Incidents

In California, legislators enacted a bill (2020 CA AB 1506) that requires an investigation by a state prosecutor for any officer-involved shooting that results in the death of an unarmed civilian. The bill also establishes a Police Practices Division within the CA DOJ and directs the Attorney General to review deadly use of force policies for law enforcement agencies upon request.

California lawmakers also enacted legislation (2020 CA AB 1185) to authorize a county to create a sheriff oversight board and an inspector general's office and further authorizes those entities to issue a subpoena when conducting an investigation of police officers or the sheriff’s department.

Enacted legislation in Connecticut (2020 CT HB 6004) allows towns to enact municipal ordinances to establish civilian police review boards. The Connecticut law also estables a state office of the inspector general to investigate police officer use of force and to prosecute any case in which the inspector general determines the use of force was unjustified or when a police officer fails to intervene or report such incident. The office of the inspector general can also make recommendations to the police standards and training board concerning censure and suspension, renewal, cancellation, or revocation of a police officer’s certification. Finally, the new law generally requires the chief medical examiner to investigate deaths of people in police or department of corrections custody.

Councilmembers in D.C. enacted legislation (2020 DC B23-0825) to amend the process for investigating complaints filed by the public against law enforcement officers through the Police Complaints Board. The new law expands the 5-member board to 9 and prohibits any member from having a current affiliation with any law enforcement agency, where previously one member of the board could be law enforcement-affiliated. The bill also expands the District’s existing Use of Force Review Board by adding new civilian voting members, including one civilian member with personal experience with the use of force by a law enforcement officer.

Legislation in Iowa (2020 IA HF 2647) authorizes the Attorney General (AG) to prosecute a criminal offense committed by a law enforcement officer, which arises from the actions of the officer resulting in the death of another person, regardless of whether the county attorney requests the assistance of the AG or decides to independently prosecute the criminal offense committed by the officer. Should the AG determine that criminal charges are not appropriate, but that an officer has violated conduct standards, the AG may refer the matter to the Iowa Law Enforcement Academy (ILEA) Council to make a recommendation to suspend or revoke the officer’s certification.

Enacted legislation in Massachusetts (2020 MA SB 2963) creates a division of police standards to investigate officer misconduct and make disciplinary recommendations to the police standards and training commission. The division of police standards shall initiate a preliminary inquiry into the conduct of a law enforcement officer if the commission receives a complaint, report, or other credible evidence that is deemed sufficient by the commission that the law enforcement officer was involved in an officer-involved injury or death; committed a felony or misdemeanor, whether or not the officer has been arrested, indicted, charged or convicted; or violated use of force standards or the duty to intervene.

Minnesota enacted legislation (2020 MN HF 1) establishes an independent Use of Force Investigations Unit in the Bureau of Criminal Apprehension (BCA). The unit is responsible for investigating all officer-involved deaths in the state as well as criminal sexual assault allegations made against peace officers. The unit expires after four years.

Legislators in Nevada enacted a bill (2020 NV SB 2) that rolls back some provisions of the state’s “Peace Officer Bill of Rights,” including repealing a statute that prohibits the inclusion of a law enforcement officer’s statements from an internal investigation in a civil case. The bill also expands the authority of an agency to conduct investigations of a police officer, including increasing the statutory limit to launch investigations from 1 year to 5 years after the incident and allowing officers to be reassigned during an investigation without their consent. Finally, the bill amends the process for investigating a police officer by only allowing for the inspection and copying of evidence after the conclusion of an investigation, instead of during the investigation.

Lawmakers in New Jersey enacted legislation (2019 NJ S 1036) that permits the Attorney General to supersede the county prosecutor of the county where the incident occurred “whenever a person’s death occurs during an encounter with a police officer or other law enforcement officer acting in the officer’s official capacity or while the decedent was in custody,” to conduct any investigation, criminal action or proceeding concerning the incident. This bill also requires that “the identity of each investigating and arresting officer shall remain subject to public disclosure.”

New York legislators also enacted a bill (2019 NY S 2574/A 1601) to establish the Office of Special Investigation within the office of the state’s Attorney General to investigate and prosecute any alleged criminal offense or offenses committed by a police or peace officer. The office is required to publish a public report in cases where it declines to present evidence to a grand jury and in cases where a grand jury declines to return an indictment.

Lawmakers in New York also passed legislation (2019 NY S 3595/A 10002) to create the Law Enforcement Misconduct Investigative Office within the office of the state’s Attorney General with broad independent oversight over police misconduct. The new office has jurisdiction to receive and investigate allegations of misconduct in any law enforcement agency within the state and is also charged with making recommendations to agencies regarding policy and practice. Additionally, any officer or employee of a law enforcement agency is required to report information concerning corruption, fraud, use of excessive force, criminal activity, conflicts of interest, or abuse of power to the office.

The Utah legislature also enacted a bill (2021 UT HB 22) to require that the state’s chief medical examiner investigate and certify the cause of death in the cases of deaths resulting directly from the actions of a law enforcement officer. The bill also creates new criminal penalties for improper certification of the cause of death under the new law and for knowingly providing false information to mislead the medical examiner.

Virginia legislators authorized (2020 VA HB 5055/SB 5035) new citizen oversight powers over local law enforcement agencies. The new law authorizes localities to establish a civilian oversight body with broad authority to receive and investigate civilian complaints regarding law enforcement conduct, investigate and issue findings on incidents regarding the conduct of officers, make binding disciplinary determinations, investigate the policies of agencies and make recommended changes, review internal investigations and issue findings on the sufficiency of such investigations, make budgetary recommendations for agencies, and issue public reports on the activities of the body. The oversight body may issue subpoenas in the performance of its duties, and current law enforcement officers are not eligible to serve on the oversight body, except that retired officers who have not previously served in the law enforcement agency within the boundaries of the locality may serve as a non-voting ex officio member.

Accountability

For as long as publicly-funded police forces have existed in the country, officers who commit brutal violence against Black people have habitually eluded any measure of accountability. Officers have been insulated from professional and judicial repercussions through layers of legal protections and collective bargaining agreements, allowing them to continue a pattern of misconduct and abuse of power against the communities they are charged to protect.

State lawmakers can strengthen accountability measures against law enforcement officers who violate standards of conduct and constitutional and civil rights by reinforcing disciplinary actions against officers, ensuring that collective bargaining agreements do not interfere with disciplinary actions, requiring public and agency access to the personnel records of officers with a history of misconduct to prevent their re-hiring, and banning qualified immunity.

Disciplinary Actions

A comprehensive police reform bill enacted in Colorado (2020 CO SB 217) requires the Colorado Peace Officer Standards and Training (POST) Board to permanently revoke the certification of a police officer who is found criminally guilty or civilly liable of unlawful use or threatened use of physical force or the failure to intervene in another officer's use of unlawful force. This law also requires POST to create and maintain a database containing information related to a police officer’s untruthfulness, repeated failure to follow POST board requirements, decertification, and termination for cause.

Enacted legislation in Connecticut (2020 CT HB 6004) expands the reasons that the police standards and training board could use to revoke a police officer’s certification to include conduct undermining public confidence in law enforcement or excessive or unjustified force. It also prohibits a decertified police officer from acquiring a security service license or performing security officer work.

The Illinois legislature passed a police criminal justice reform bill (2021 IL HB 3653) that creates a more robust certification system and lays out standards and processes for decertification of police officers, including the option to do so for exercising excessive use of force or failing to intervene to stop another officer from excessive use of force. The new law also expands accountability across police departments by requiring the permanent retention of police misconduct records and removes the sworn affidavit requirement when filing police misconduct complaints.

Indiana enacted legislation (2021 IN HB 1006) to establish a procedure to allow the Indiana law enforcement training board to decertify an officer who has committed misconduct. It also provides that decertification proceedings may continue for a police officer who resigns or retires before a finding and order have been issued concerning a violation. Another section of the law requires an agency hiring a law enforcement officer to request the officer's employment record and certain other information from previous employing agencies, requires the previous employing agency to provide certain employment information upon request, and provides immunity for disclosure of the employment records.

Legislation enacted in Iowa (2020 IA HF 2647) established circumstances under which the Iowa Law Enforcement Academy (ILEA) Council is required to revoke, or may suspend or revoke, a certification of a law enforcement or reserve police officer, and when the ILEA may deny an application of a law enforcement officer from another state seeking employment at a law enforcement agency in the state.

Kentucky enacted legislation (2021 KY SB 80) to include unjustified excessive or deadly force as a form of professional malfeasance that can lead to termination and decertification as a police officer.

Maryland legislation (2021 MD HB 670) allows for the suspension or revocation of a police certification for violating use of force laws and requires the revocation for a police officer who was previously fired or resigned while being investigated for serious misconduct or use of excessive force.

Legislation in Massachusetts (2020 MA SB 2963) creates a mandatory certification process for police officers through the Massachusetts Peace Officer Standards and Training Commission (POST). The Commission, through a majority civilian board, will certify officers and create processes for decertification, suspension of certification, or reprimand in the event of certain misconduct, including excessive use of force or use of a chokehold.

In New Mexico, the state legislature passed and enacted a bill (2020 NM SB 8) that would require a police officer’s certification to be permanently revoked if they are convicted or if they plead guilty to a crime of unlawful use of force, threatened unlawful use of force, or failing to intervene when unlawful use of force occurs. It also establishes that police officers who do not comply with body camera requirements are presumed to be acting in bad faith.

Lawmakers in Utah enacted legislation (2021 UT HB 62) to expand the authority of the state’s Peace Officer Standards and Training Council to take disciplinary action, including decertification, against a peace officer for “conduct that involves dishonesty or deception” in violation of agency policy or state or federal law, and for engaging in “biased or prejudicial conduct” based on “race, color, sex, pregnancy, age, religion, national origin, disability, sexual orientation, or gender identity.”

Legislation (2020 VA HB 5051) enacted in Virginia expands the existing statutory process for the decertification of officers to require that agencies notify the state Criminal Justice Services Board when a law enforcement officer is terminated or resigns for engaging in serious misconduct, while under investigation for serious misconduct, or for an act that constitutes exculpatory or impeachment evidence in a criminal case. The bill also requires notice when an officer is terminated or resigns for violating a state or federal law or in advance of being convicted of a felony offense. Existing law only required notification to occur when officers resign in advance of a decertification offense or a pending drug screening. Finally, the bill authorizes the Criminal Justice Services Board to initiate decertification proceedings against current law enforcement or jail officers for such activities, where the Board was previously only authorized to initiate proceedings against former officers for failing to comply with training requirements.

Collective Bargaining Agreements

Enacted legislation in Connecticut (2020 CT HB 6004) explicitly prohibits police union collective bargaining agreements (CBAs) from barring disclosure of certain disciplinary actions, and it specifies that the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) prevails over contrary CBA provisions.

The D.C. Council passed legislation (2020 DC B23-0825) that amends existing law to require that “all matters pertaining to the discipline of law enforcement personnel shall be retained by management and not be negotiable,” which explicitly applies to “any collective bargaining agreements entered into with the Fraternal Order of Police/Metropolitan Police Department Labor Committee after September 30, 2020.”

Legislation in Maryland (2021 MD HB 670) repeals the Law Enforcement Officers’ Bill of Rights in its entirety and establishes new provisions relating to police accountability and discipline. A law enforcement agency may not negate or alter any of the requirements relating to specified police officer accountability and discipline through collective bargaining.

Oregon lawmakers passed a bill (2020 OR SB 1604) that would limit the likelihood that disciplinary actions taken against a law enforcement officer by the agency are later reversed or reduced through binding arbitration. Under the new law, if an arbitrator makes a finding on officer misconduct that is consistent with the agency’s findings, the arbitration award may not order action that differs from the disciplinary action imposed by the agency. The bill also establishes a “discipline guide” or “discipline matrix,” which outlines the parameters of discipline for acts of misconduct, to be adopted into the agency’s disciplinary policy as the result of a collective bargaining agreement.

Personnel Records and Hiring

Recent legislation in Arkansas (2021 AR HB 1197) requires any notice of separation sent to the Law Enforcement Commission on Standards and Training to include, if applicable: (1) the law enforcement officer retired while the subject of a pending internal investigation; (2) the law enforcement officer was separated due to excessive use of force, and/or (3) the law enforcement officer was separated for dishonesty or untruthfulness.

In D.C., councilmembers enacted legislation (2020 DC B23-0825) that renders any applicant ineligible for appointment as a sworn member of the Metropolitan Police Department if they were previously determined to have committed serious misconduct, terminated or forced to resign for disciplinary reasons, or resigned to avoid disciplinary action or termination.

Hawaii passed a law (2019 HI HB 285) that requires county police departments to disclose to the Legislature the identity of an officer upon an officer's suspension or discharge, and it allows for public access to information about suspended officers. The law also authorizes the law enforcement standards board to revoke certifications and requires the board to review and recommend statewide policies and procedures relating to law enforcement, including the use of force.

Lawmakers in Maryland enacted a bill (2021 MD HB 670) to require an individual who applies for a position as a police officer to disclose to the hiring law enforcement agency all prior instances of employment as a police officer and to authorize the hiring law enforcement agency to obtain the police officer’s full personnel and disciplinary record from each law enforcement agency that previously employed the police officer.

Massachusetts lawmakers passed a bill (2020 MA SB 2963) to create a publicly available, online database of decertification, suspension, and retraining orders that includes the names of all decertified or suspended officers, the date of decertification, or beginning and end dates of the suspension, the officer’s last appointing agency, and the reason for decertification or suspension. Additionally, the police standards and training commission shall cooperate with the national decertification index and other states and territories to ensure officers who are decertified by the commonwealth are not hired as law enforcement officers in other jurisdictions, including by providing the information requested by those entities.

A bill enacted in New Jersey (2020 NJ AB 744) requires that if law enforcement agencies consider appointing new officers with prior law enforcement experience, the hiring agency must request the applicant’s files from their previous law enforcement employers, including internal affairs and personnel files. The law also requires the other agencies to provide the information about the applicant to the hiring agency.

A bill passed in New York (2020 NY S 8496/A 10611) repealed a section of existing law that previously allowed law enforcement agencies to refuse to disclose personnel records. Under the new law, the disciplinary records of law enforcement officers can be requested through the state’s Freedom of Information Law, with redactions for personal or sensitive information.

Oregon legislators approved a bill (2020 OR HB 4207) to establish an online public database of records on officers whose certifications have been revoked or suspended. The bill also requires law enforcement agencies to request and review personnel records from all prior law enforcement agency employers of prospective applicants before extending an offer of employment.

In Pennsylvania, lawmakers unanimously passed a bill (2020 PA HB 1841) to create a statewide database with the separation records of law enforcement officers and requires agencies to complete a hiring report if prospective hires have a separation record including certain incidents, including the use of excessive force and discrimination. The bill also establishes new requirements for law enforcement agencies to conduct background investigations on applicants, including past separation records. Under the new law, agencies are required to provide employment information on applicants who are the subject of a background investigation upon request by a prospective employing law enforcement agency.

The Utah legislature enacted a bill (2021 UT SB 13) to increase reporting requirements to the state’s Peace Officer Standards and Training Council in cases where a law enforcement officer’s employment terminates during certain internal investigations. The bill also creates new requirements of law enforcement agencies and training academies to provide information about an applicant upon request.

Qualified Immunity

A comprehensive police reform bill enacted in Colorado (2020 CO SB 217) allows a person who has had their constitutional rights infringed upon by a police officer to bring civil action for the violation and provides that qualified immunity is not a defense to the civil action. Additionally, if the police officer’s employer determines the officer did not act in good faith and with a reasonable belief that the action was lawful, the police officer is personally liable for 5% of the judgment up to $25,000.

Comprehensive policing reform legislation in Connecticut (2020 CT HB 6004) establishes a civil cause of action against police officers who deprive an individual or class of individuals of the equal protection or privileges and immunities of state law, and it eliminates governmental immunity as a defense in certain lawsuits.

In New Mexico, state legislators enacted the “New Mexico Civil Rights Act” which allowed people to claim deprivation of any “rights, privileges, and immunities” guaranteed by the New Mexico Bill of Rights and to sue for damages in state district courts. This law requires these people to file suit against the public body itself and not the individual employed by the public body. This law also explicitly prohibits public bodies and those acting on the public body’s behalf from using qualified immunity as a defense.

System Oversight

The violent realities of over-policing in Black communities and other communities of color are well-known by their residents, who are also best-positioned to develop the policy solutions necessary for lasting transformational change. But too often, state legislatures and institutional actors responsible for enacting policy change are not equitably representative of their communities, and therefore lack the lived experience and information necessary to make structural changes to policing systems.

At the state level, lawmakers can pave the way for broader changes by ensuring that communities have adequate access to data and oversight entities with decision-making power. State legislators can ensure that future reform efforts are informed by publicly available and disaggregated information on police interactions. Comprehensive data collection drives continuous oversight by identifying and investigating patterns of policing conduct that disproportionately harm communities of color. Legislators can also establish independent oversight bodies charged with reenvisioning policing and making policy recommendations with strong requirements for meaningful community participation.

Data Collection

A comprehensive police reform bill enacted in Colorado (2020 CO SB 217) requires the division of criminal justice in the department of public safety to collect and maintain a searchable, online database of aggregated data by state or local law enforcement agency on contacts conducted, unannounced entry, or use of force by police officers, as well as instances of police officers resigning while under investigation for violating department policies.

New York legislators passed a bill (2019 NY S 1830/A 10609) to create new data reporting requirements on misdemeanors and arrest-related deaths. Under the bill, law enforcement agencies are required to report arrest-related deaths to the Division of Criminal Justice Services, and the collected data must be made available online and updated monthly. The bill also requires the chief administrator of the courts to maintain an online database of the outcomes of misdemeanor offenses and violations, disaggregated by race, ethnicity, age, sex, and county.

A bill (2020 VA HB 1250) enacted by legislators in Virginia prohibits “biased-based profiling” by law enforcement officers. The bill also creates new race and ethnicity data collection requirements for traffic stops by Virginia State Police officers, and creates a uniform statewide database for traffic stops, excessive force complaints, and other information collected by law enforcement agencies. The data analysis shall be used to determine the existence and prevalence of the practice of bias-based profiling and the prevalence of complaints alleging the use of excessive force.

Pattern or Practice Investigations

Comprehensive reform legislation enacted in Colorado (2020 CO SB 217) makes it unlawful for any governmental authority to engage in a pattern or practice of conduct by police officers that deprives individuals of rights, privileges, or immunities secured or protected by the constitution or laws of the United States or the state of Colorado. Whenever the state attorney general has reasonable cause to believe that a violation of this provision has occurred, the state attorney general may in a civil action obtain any and all appropriate relief to eliminate the pattern or practice.

Massachusetts police reform legislation (2020 MA SB 2963) refer patterns of racial profiling or the mishandling of complaints of unprofessional police conduct by a law enforcement agency for investigation and possible prosecution to the attorney general or the appropriate federal, state or local authorities. If the attorney general has reasonable cause to believe that such a pattern exists based on information received from any other source, the attorney general may bring a civil action for injunctive or other appropriate equitable and declaratory relief to eliminate the pattern or practice.

Under a bill (2020 VA SB 5024/HB 5072) passed by Virginia lawmakers, the state Attorney General is authorized to investigate law enforcement agencies for unlawful patterns or practice of conduct, such as racially biased policing patterns or excessive force, and to seek remedy through civil action or by entering into a court-enforceable conciliation agreement with the agency. Agencies that are found to be out of compliance with conciliation agreements are also subject to a loss of state funding.

Independent System Oversight

The D.C. Council enacted legislation (2020 DC B23-0825) to establish the Police Reform Commission to examine policing practices and provide recommendations for reforming and revisioning policing. Required members of the 20-member Commission includes criminal and juvenile justice reform organizations, Black Lives Matter DC, student- or youth-led advocacy organizations, returning services organizations, and returning citizen organizations. The new law does not include District law enforcement agencies on the Commission, but does not prohibit past affiliation with law enforcement agencies for eligibility as a member.

A bill (2020 OR HB 4201) passed by Oregon lawmakers establishes the Joint Committee on Transparent Policing and Use of Police Reform to examine and make recommendations to the legislature regarding policies to reduce the use of force by police officers and improve transparency in the investigation of its use.

Local and National Organizations

Many Black-led and centered organizations have been leading on policing, police reform, and abolition for years. We encourage you to seek information and support from this list below. Note this is not a comprehensive list and will be updated.

National

- The Movement for Black Lives

- Campaign Zero

- Mapping Police Violence

- African American Policy Forum

- Black Women’s Blueprint

- Law for Black Lives

- The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights

- NAACP

- NAACP Legal Defense Fund

- National Urban League

- Race Forward

- Advancement Project

- Center for Policing Equity

- Policing Project at NYU School of Law

- Transform Harm

- A World Without Police

- Color of Change

- Forward Together

- The Million Hoodies Movement for Justice

- ABFE: A Philanthropic Partnership for Black Communities

- Bill of Rights Defense Committee

- Freedom to Thrive

Minnesota

- Black Visions Collective

- Communities United Against Police Brutality

- Minnesota Freedom Fund

- Minnesota Justice Coalition

- Northstar Health Collective

- Reclaim the Block

- Unicorn Riot

Other States

- Baltimore United For Change (Maryland)

- Communities United for Police Reform (New York)

- The Dream Defenders (Florida)

- Just Georgia Coalition (Georgia)

- Louisville Community Bail Fund (Kentucky)

- Safety Beyond Policing (New York)

- NAACP local chapters

- National Urban League local affiliates

- Hands Up United (Missouri)

- Assata's Daughters (Illinois)

- Safe Streets/Strong Communities (Louisiana)

- Youth Justice Coalition (California)

- Anti-Police Terror Project (California)

Resources

- A Vision for Black LIves: The Demilitarization of Law Enforcement, Including Law Enforcement in Schools, College Campuses, and Medical Facilities, The Movement for Black Lives

- Vision for Justice 2020 and Beyond: A New Paradigm for Public Safety Overview, The Leadership Conference and Civil Rights Corps

- Alternatives to Police Services, Defundthepolice.org

- Defund Police (video), Project NIA

- Yes, We Mean Literally Abolish the Police, Mariame Kamba in the New York Times

- The Case for Violence Interruption Programs as an Alternative to Policing, Data for Progress and the Justice Collaborative Institute

- 8toabolition.com

- Justice Reform, Progressive Caucus Action Fund

- Reforms Introduced to Protect the Freedom of Assembly, International Center for Not-for-Profit Law

- US Protest Law Tracker, International Center for Not-for-Profit Law

- Legislative Responses for Policing-State Bill Tracking Database, National Conference of State Legislatures

- No More Half Steps: We Demand Real Change to End Police Violence, Communities United Against Police Brutality

- The Case for Self-Enforcing Streets, Transportation Alternatives

- Police “Reforms” You Should Always Oppose, Transform Harm

- Reformist Reforms vs. Abolitionist Steps in Policing, Critical Resistance

- Reading Towards Abolition: A Reading List on Policing, Rebellion, and the Criminalization of Blackness, The Abusable Past

- Freedom to Thrive: Reimagining Safety & Security in Our Communities, Center for Popular Democracy

- Beyond Policing, The Opportunity Agenda