About This Primer

This primer is part of a series on anti-racist state budgets. To understand the concept of creating anti-racist state budgets, it is important to understand the difference between racist and anti-racist ideas and policies. The following excerpts are from How to Be an Antiracist (2019) by Ibram X. Kendi:

Racist vs. Anti-racist Ideas

A racist idea is any idea that suggests one racial group is inferior or superior to another racial group in any way. Racist ideas argue that the inferiorities and superiorities of racial groups explain racial inequities in society. . . . An antiracist idea is any idea that suggests the racial groups are equals in all their apparent differences – that there is nothing right or wrong with any racial group. Antiracist ideas argue that racist policies are the cause of racial inequities.

Racist vs. Anti-racist Policies

A racist policy is any measure that produces or sustains racial inequity between racial groups. An antiracist policy is any measure that produces or sustains racial equity between racial groups. . . . There is no such thing as a nonracist or race-neutral policy. Every policy in every institution in every community in every nation is producing or sustaining either racial inequity or equity between racial groups.

For additional race-equity concepts and definitions, please visit the Racial Equity Tools glossary.

The following primer examines how policymakers have impacted low-income communities and communities of color through racist transportation policies and practices and, drawing from existing research, analyzes how state budgets can guide racial equity outcomes. It also outlines progressive considerations for state legislators to take into account when crafting related anti-racist legislation. We hope that a better understanding of the effects of state budgets on transportation equity will support progressive legislative efforts to create transportation systems that promote public health, sustainability, and equitable opportunity.

History of Racist Transportation Policies

Our ability to access affordable and reliable transportation is a basic right that many communities have been deprived of as a result of inequitable transportation investments. Low-income communities and communities of color bear the largest burden of our states’ transportation decisions.

Race and transportation have long been intertwined. In 1955, Rosa Parks became the icon of the Montgomery Bus Boycott by refusing to give up her bus seat to a white rider. Her arrest led Montgomery’s Black community to launch a massive boycott, demanding better treatment for Black riders and equitable access to public transit. In the early 1960s, Freedom Riders challenged segregation laws and asserted their rights to ride interstate transportation.

Although the civil rights movement helped increase the accessibility of transportation, the issue of inequity has persisted. Discriminatory practices, such as redlining, have locked communities of color out of certain neighborhoods and left them without many transportation options. Redlining was followed by other detrimental efforts, such asurban renewal—a nationwide program established by the Housing Act of 1949—that provided federal grants to cities for the purposes of rebuilding their downtowns.

Urban renewal allowed cities to raze and rebuild entire areas, clear slums and blighted properties, and develop highways. This program led to the widespread development outside city centers, also known as urban sprawl. Investments in these developments have changed the urban geographical landscape and displaced communities, disproportionately impacting low-income people and people of color. Similar racist policies and practices persisted after the 1960s and continue today, leading to increased traffic congestion and air pollution, ongoing negative health effects (e.g., respiratory illnesses, lung cancer, and impaired lung development), evictions of marginalized groups, dangerous road conditions for biking and walking, and the destruction of thriving neighborhoods.

Current departments of transportation and transit agencies are still operating systems grounded in racism and guided by the inequitable policies of the civil rights era. Not only do current highway projects continuously displace Black and Brown communities across the country, but also transit agencies have designed their routes and systems around the stereotype that there are only two kinds of riders: “captive” and “choice” riders, with this binary design disproportionately disadvantaging marginalized communities.

Choice Riders vs. Captive Riders

“Choice” riders—who are mostly affluent individuals with cars—are not transit dependent but often want fast, reliable, comfortable transportation with great service. “Captive” riders—who are mostly low-income people without cars—are those who rely on transportation services even if they are unhappy with the service. Categorizing transit this way has led policymakers to prioritize transit projects that place greater burden on communities of color.

In some cities, transit agencies have isolated commuter buses and local buses that reach the same destination by creating vastly different bus routes based on the socioeconomic demographics of the neighborhoods. Oftentimes, such separation of transit networks creates more barriers for low-income, mostly Black “captive” riders who cannot afford the higher-quality bus service and must travel longer to get to their destinations. Agencies have also relied on the police to patrol trains and enforce fares, resulting in increased enforcement that disproportionately impacts people of color and criminalizes poverty.

Impacts on Marginalized Communities

Development of Highways & Displacement of Communities

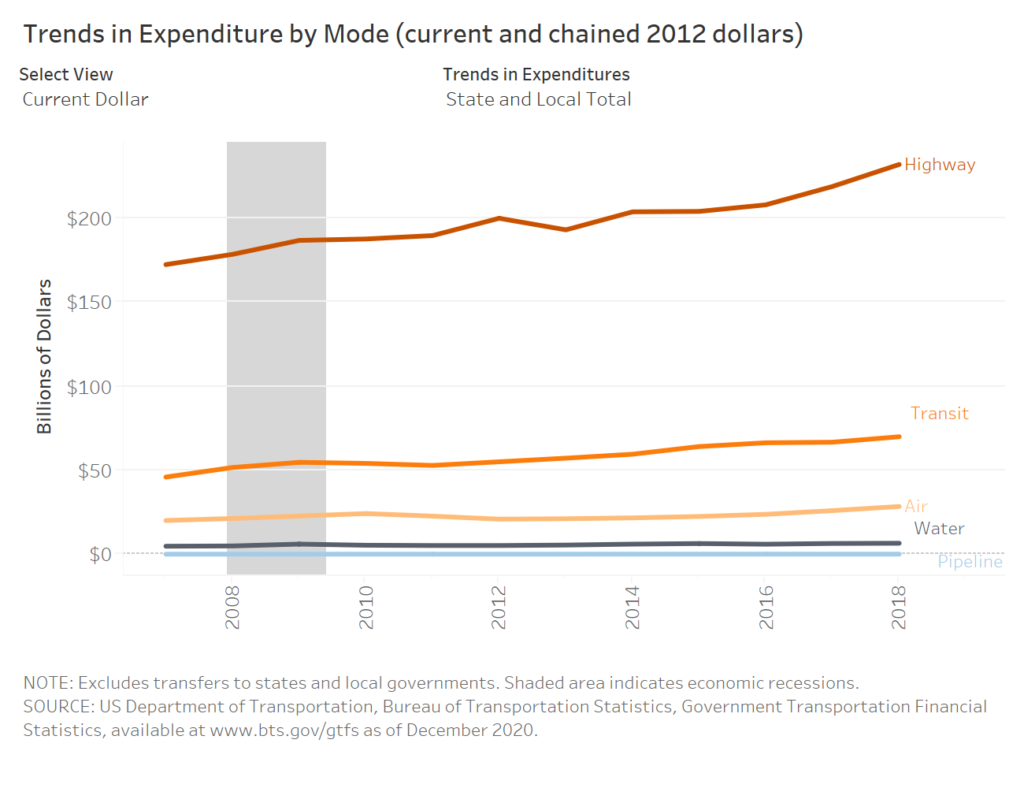

In 2018, state and local governments collectively spent about $70 billion on public transportation. At the same time, these governments devoted over $232 billion to highways. Greater investment in highways is one of many examples of how transportation policy priorities have led to an underinvestment in sustainable infrastructure within marginalized communities.

Many highway construction projects have also displaced communities by creating changes in the land value of a neighborhood and destroying the units occupied by low-income households and households of color. These projects contribute to a loss of affordable housing and the disintegration of communities, significantly affecting the quality of the neighborhood and its residents. Similar to the ways urban renewal programs destroyed the homes of marginalized communities to resolve urban blight, the prioritization of highway expansion over public transportation projects has inequitable and disproportionate effects on low-income and minority residential neighborhoods.

Accessibility of Public Transit

Financial Accessibility

Since 1995, public transit ridership has increased by 28%. Contributing to this ridership increase, income and wealth disparities have led many people of color to have relatively less access to cars. As a result, people of color are the ones most likely to rely on public transportation as their main form of travel. Especially in urban areas, Black, Latinx, and Asian people take public transit more often than their white counterparts to access public services and get to work and school. However, the restriction of public funds for transit, along with governments’ prioritization of highways, has shifted resources away from alternative transportation options. If and when municipalities rely on fare increases to manage their budget crises, these increases hurt transit-reliant communities and decrease the financial accessibility of buses. Cities and states can mitigate these issues if they make targeted investments in public transit. One study in Boston found that a 50% reduction in transit-pass costs for low-income riders resulted in about 30% more trips and an increase in trips to health care and social services.

Physical Accessibility

Forty-five percent of Americans have no access to public transportation. Some areas, especially sprawling cities, do not support public transportation due to certain land patterns and the separation of homes from places of work and services, creating longer travel distances and a greater dependence on automobiles. Residents in these areas are then forced to rely on cars, which is an expense many cannot afford, leaving them with few good transportation options and compounding the cycle of poverty. Low-income people of color are already less likely to own a car and their lack of car ownership combined with inadequate and inaccessible public transit further exacerbates their circumstances. Even when people are presumed to have access to transit, these individuals often have to navigate dangerous roadways in order to do so. For more information on the impacts of dangerous road infrastructure, see the section below on Road Safety for Civilians.

Note on Ableism

In addition to people of color, the disabled community has historically been excluded from public transportation. Thirty years after the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), transportation choices for people with disabilities are still limited. From transit stop and station designs that assume passengers will be able-bodied (e.g., lack of shade or stairs to platforms) to lack of compliance with ADA requirements for announced bus stops, there are many important issues to address when improving the accessibility of bus services for all. Lack of transit-oriented development—“walkable, compact, mixed-use, higher-density development within walking distance of a transit facility”—places a burden on those who cannot drive due to a physical disability, visual impairment, or other reasons.

Privatization Risk

Many cities and transit agencies are partnering with ride-hailing companies, such as Uber and Lyft, to make transportation more affordable and connect more riders to transit hubs through a mobile application that could connect users to cars, bikes, scooters, buses, and trains. Some agencies have already replaced routes with low ridership with credits for Uber and Lyft. While such partnerships will help invite more riders to use these ride-hailing applications, these agreements with Uber and Lyft have many technological, financial, and cultural implications for non-native English speakers and people without access to banks, smartphones, and data plans.

Road Safety for Civilians

Walking, bicycling, and public transit need to be not only accessible to but also safe for everyone. Motor vehicle crash data comparing 2010 to 2019 shows that in urban areas, pedestrian fatalities increased by 62% and bicyclist fatalities increased by 49%, and the proportion of total traffic fatalities that were non-occupant (e.g., bicyclists and pedestrians) fatalities jumped from 15% in 2010 to 20% in 2019. Similar to how states are not investing in public transit, states are also allocating only a small portion of their budgets to improve pedestrian infrastructure. People of color and low-income people often use active transportation to get from one place to another, with Hispanic, African American, and Asian American populations experiencing the fastest growth in bicycling. Yet the street conditions are often more dangerous for these individuals in comparison to the walking and bicycling conditions of their white, middle-class counterparts.

People of color are already twice as likely to be killed while walking than other groups. Not only do high-speed, multi-lane avenues and poorly designed streets contribute to traffic-related deaths, but they also affect the abilities of communities, especially those composed of low-income individuals and people of color, to be physically active. These conditions have the potential to shorten lives and impair people’s ability to thrive.

Environmental Effects on Public Health

The transportation sector emits more than half of the nitrogen oxides in our air and accounts for about 28% of total U.S. greenhouse gas emissions. Urban and metropolitan areas with traffic congestion typically experience the most significant pollution, which is often traced to inefficient land use patterns, sprawling development, and policies that favor highway development over transit. Long-term exposure to pollutants can lead to lung cancer, heart disease, respiratory illnesses, and impaired lung development and function in children and infants. These issues are further compounded when unsustainable transportation projects invade communities where poor air and water quality is already an issue. Oftentimes, it is low-income neighborhoods and communities of color who face greater environmental and health consequences from the underinvestment in sustainable transportation infrastructure.

Traffic Enforcement and the Role of Police

Instead of investing in equitable transportation projects, 25 states have used portions of their state highway fund dollars to finance highway patrols as of 2017. Dedicating highway fund dollars for state police not only takes away funding for more equitable transit, but also severely affects people’s ability to benefit from the transportation system. Transportation inequities take place in low-income communities and communities of color, which are often over-policed and under-protected in comparison to higher-income, majority-white neighborhoods.

State and local law enforcement compound such inequities by using traffic laws and minor violations as a pretext for stopping and searching drivers, especially people of color. Coupled with racial bias, these stops often escalate and lead to unnecessary use of force or arrests that disproportionately impact Black people and communities of color. In addition, disparate targeting of fare evasion enforcement on transit systems has led to increased police-civilian interaction for harmless infractions and the criminalization of poverty in Black and Brown neighborhoods.

Policy Considerations

When planning and proceeding with transportation projects, states should promote equity and prioritize community needs by evaluating accessibility in transportation planning decisions and considering the following recommendations:

- Incorporate inclusive community engagement practices into transportation planning and decision-making processes. Low-income communities and communities of color bear most of the burden of unsustainable transportation outcomes yet have been historically excluded from the decision-making process. Communities should have the power to decide which transportation projects best meet their needs. Thus, state legislators and departments of transportation should sustain avenues for increased public involvement in transportation planning so communities can directly influence transportation priorities, choices, and budget allocations.

- Develop a mechanism for prioritizing and evaluating transportation projects based on sustainability, accessibility, and community priorities. Car-centric transportation planning often result in policies that physically, economically, and environmentally harm low-income communities and communities of color. To better serve those most impacted by transportation projects, state legislators should create a prioritization process that integrates equity principles and considers community needs.

Example of prioritizing equity and community needs

Virginia’s legislature unanimously passed 2014 VA HB 2 (Chapter 726), which directed the Commonwealth Transportation Board (CTB) to develop and use a prioritization process to select transportation projects and ensure the best use of limited tax dollars. The bill led the CTB to develop SMART SCALE, a data-driven system that scores projects based on an objective, outcome-based process that is transparent to the public. Factor areas include safety, congestion mitigation, environmental quality, economic development, land use, and accessibility. “Accessibility” considers projects that will ensure access to jobs for disadvantaged groups. The results from the screening process are presented to the public, and the CTB takes public comments into account when selecting transportation projects.

- Increase funding for public transportation to provide and maintain quality and affordable transit facilities and services, especially for transit-dependent communities. Currently, many states rely on outdated technology, tools, and policies to inform their decisions on which transportation projects to prioritize and fund. For example, some states prioritize highway projects because they have constitutional prohibitions that limit the use of gas tax revenues to highways only. To ensure equitable investments in public transportation, state legislators should reallocate funding toward sustainable modes of infrastructure by modernizing the policies and systems of their departments of transportation.

Infrastructure Funding

When seeking out revenue sources for public transportation, state legislators need to also evaluate the potential implications of these sources for marginalized communities. The funding source, mechanism, and revenue distribution must all center equity. States’ most important source of transportation funding is state gas taxes. There are many states that have waited a decade or longer to increase their gas tax rates. In addition, some states’ taxes have not been adjusted to keep pace with rising transportation construction costs, negatively affecting funding of economically vital infrastructure projects. When boosting funding for public transportation through gas tax reform or other types of taxes (e.g., vehicle miles traveled tax and congestion pricing), state lawmakers must also reduce regressivity and protect low-income communities from bearing the largest financial burden.

Examples and resources of revenue options

Example: Passed in 1935, Colorado’s constitutional amendment required gas tax revenues and vehicle registration fees to be spent on highways and bridges. However, the state had an unclear definition of “highways,” largely excluding local roads, sidewalks, bike infrastructure, and transit. In 2013, a coalition of transit advocates helped push for 2013 CO SB 48 (Chapter 138) (CO Stat. §§ 43.4.205,43.4.207,43.4.208), which expanded the interpretation of “highways” and allowed for the entire local share of the Highway Users Trust Fund (derived from state gas tax and registration fees) to be used for public transit and bicycle or pedestrian investments.

Example: In 2007, Minnesota legislators passed a transportation funding bill (2007 MN HF 2800) that included a gas tax increase. To offset the impacts of the increase on low-income communities, the bill also created a lower-income motor fuels tax credit equal to $25 to assist those in the lowest income bracket. However, three years later, the legislature repealed this tax credit through 2010 MN HF 2695 [Section 62(a)].

Resource: The National Conference of State Legislatures has outlined 2013-2020 legislative actions on changing and reforming state gas taxes.

Resource: This resource from American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy covers state legislation that identifies specific sources of funding for public transit and other alternatives to highway modes of transportation.

Resource: The Greenlining Institute’s Greenlined Economy Guidebook focuses on six standards for equitable community investment: 1) emphasize race-conscious solutions, 2) prioritize multisector approaches, 3) deliver intentional benefits, 4) build community capacity, 5) be community driven at every stage, and 6) establish paths to wealth building. These standards can help legislators make equitable community-based decisions on transportation projects.

- Address our crumbling roadway infrastructure by reallocating funds from highway construction projects to maintenance and infrastructure that benefit disadvantaged communities. Federal law provides states with the flexibility to spend funds they receive from highway formulas. However, such flexibility grants the states the ability to focus on expanding highways instead of fixing crumbling roads first. While it is critical to put pressure on Congress to prioritize highway formula dollars for maintenance, states can also take immediate action by ensuring their statewide transportation packages emphasize repairing potholes, unfixed highways, and crumbling roads over expansion projects. State legislators should also devote a percentage of their transportation funds to low-income or high-need communities.

In addition, policymakers should consider implementing life cycle cost analysis (LCCA) programs. Such programs enable transportation planners to examine the total costs of a project over its expected life and compare differing life-cycle costs between alternative options. As a result, LCCAs help identify the most beneficial and cost-effective projects and require decision-makers to think more about maintenance over expansion.

Examples of reallocating funds and LCCAs

Example: In 2013, California enacted 2013 CA SB 99 (Chapter 359), which created an Active Transportation Program (ATP). Although the law expressly requires that 25% of funds must benefit disadvantaged communities, the program has seen more than 85% of funds devoted to projects that support high-need neighborhoods. Since its inception, ATP has funded over 800 active transportation projects in both urban and rural areas across the state. Through 2017 CA SB 1 (Chapter 5), California later allocated an additional $100 million per year in funding to ATP.

Example: In 2008, Minnesota enacted 2008 MN HF 3486 / Section 71 (Chapter 287) (MN Stat. § 174.185), which requires an LCCA for every project in the reconditioning, resurfacing, and road repair funding categories. Documentation required includes the lowest life-cycle cost, any alternatives considered, as well as a justification for the chosen strategy if it does not include the lowest life-cycle cost option.

- Support transit-oriented development and smart growth initiatives that promote community economic development and incorporate equity principles. Transit-oriented development promotes alternative modes of sustainable transportation and increases access to affordable housing, jobs, and schools for low- and moderate-income families. State legislatures should:

- create incentives for integrated transportation planning and land use that enables all people to experience the benefits of pedestrian-oriented development near transit hubs;

- address land-use concerns that inhibit transit-oriented development and allow cities to take meaningful action in their municipalities; and

- use racial equity outcomes to guide the planning process and ensure that such development does not displace and evict long-term and low-income residents.

Example and resources for transit-oriented development

Example: Delaware passed a bill (2016 DE SB 130) allowing the state department of transportation to enter into an agreement with local governments to create transit-oriented development districts, or “Complete Community Enterprise Districts,” allowing municipalities and agencies to collaborate and create stronger active transportation infrastructure to improve access to transit.

Resources:

- Reconnecting America released a report of state, regional, and local programs that fund transit-oriented development plans and projects.

- PolicyLink posted a report on advancing equitable transit-oriented development through community partnerships and public sector leadership.

- Enterprise, the National Housing Trust, and Reconnecting America present case studies that focus on ways to preserve affordable housing near transit.

- The National Conference of State Legislatures has a resource on transit-oriented development in the states.

6. Call on municipalities to adopt and implement Complete Streets policies in low-income, high-need communities. Designing transit-friendly streets and safe roadways for all users will make walking and biking safer and more convenient for pedestrians and cyclists. Complete Streets policies promote infrastructure that reduces reliance on cars, resulting in increased engagement in physical activity and a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. State legislators should encourage the implementation of this policy in high-need communities that have more dangerous street conditions.

Example and resource for Complete Streets policies

Example: The Massachusetts Department of Transportation’s Complete Streets Funding program was created by legislative authorization through a Transportation Bond Bill (2014 MA HB 4046 / Section 9 (Chapter 79)). The program provides technical assistance and construction funding to eligible municipalities that demonstrate a commitment to embedding Complete Streets in policy and practice.

Resource: The National Association for City Transportation Officials has an Urban Street Design Guide that serves as a blueprint for designing 21st century streets and that charts the principles and practices for making streets safer and more livable in the United States.

7. Redirect funds and responsibilities away from state police and toward investments in communities. Legacies of discrimination and racism pervade our transportation system and policies. Not only do communities of color have a lack of access to mobility options, but they also suffer disproportionately from police-involved violence initiated by traffic stops. In order to achieve transportation equity and ensure safe streets for all populations, states must address both policies that disadvantage biking and walking and the ongoing racist police enforcement of traffic laws that lead to disproportionate harms for Black and Brown drivers.

Examples of alternatives to policing

Example: In 2019, the New York legislature passed 2019 NY AB 6449 (Chapter 30), which granted New York City’s Department of Transportation the authority to expand and enhance its school-based speed camera program from 140 locations to 750. When installation is completed, the city will have the largest automated enforcement program in the United States.

Example: In 2020, Berkeley, California, passed a first-in-the-nation plan to create a newly formed Department of Transportation to replace police officers with a group of unarmed employees who will enforce traffic laws. The city is also establishing a community engagement process to develop a new model for policing in Berkeley.

Additional Resources

Urban Sprawl and Highway Expansion

- Rethinking Urban Sprawl: Moving Towards Sustainable Cities, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

- Measuring Sprawl 2014, Smart Growth America

Transit Accessibility

- To Move Is to Thrive: Public Transit and Economic Opportunity for People of Color, Demos

- Equity in Transportation for People with Disabilities, American Association of People with Disabilities

Environmental and Public Health Impacts

- How Transportation Planners Can Advance Racial Equity and Environmental Justice, The Urban Institute

Active Transportation and Pedestrian Safety

- Right of Way: Race, Class, and the Silent Epidemic of Pedestrian Deaths in America, Angie Schmitt

- The Elements of a Complete Streets Policy, Smart Growth America

- At the Intersection of Active Transportation and Equity, Safe Routes to School National Partnership

Effects of Traffic Enforcement

- Reduce the Role of Police in Traffic Enforcement for the Safety of Everyone, California Bicycle Coalition

- The Case for Self-Enforcing Streets, Transportation Alternatives

Racial Equity and Transportation