Key Trends

- Increasing racial data transparency through improved data collection and analysis.

- Improving access to health care through telehealth expansion.

- Expanding Medicaid and insurance coverage to address health disparities.

Introduction

Racial disparities in health coverage, chronic health conditions, mental health, and mortality persist across the United States. Racism has led to the deeply entrenched inequality within our country’s healthcare, economic, and social systems that perpetuate these health disparities and inequities. Such inequity becomes magnified in times of national hardship, such as the unprecedented global pandemic and economic recession we are currently experiencing.

The CDC COVID Data Tracker indicates that there have been around thirty million known COVID-19 cases in the United States, and the virus has killed around 500,000 people as of the end of February 2021. Although COVID-19 does not discriminate along racial or ethnic lines, racial, ethnic, and Indigenous communities are more vulnerable to the pandemic. The compounding effect of existing inequities put Black and Brown people, communities of color, Indigenous people, and other marginalized groups at greater risk of infection and death.

For example, these communities:

- Experience higher risks of developing chronic health conditions, like obesity and asthma;

- Are disproportionately concentrated in employment sectors and occupations that are highly vulnerable (e.g. farmworkers, grocery workers, transit operators);

- Are more likely to rely on public transit as their main form of transportation and face the risk of contracting COVID-19 in a crowded bus;

- Often face challenges with accessing nutritious and healthy food;

- Have limited safe, affordable housing choices and often live in overcrowded housing;

- Make up a disproportionate percentage of the population in prisons, which account for many of the hot spots of COVID-19 infections;

- Are more likely to experience discriminatory behavior by healthcare professionals and receive lower quality care than their white counterparts; and

- Have less access to health insurance, quality medical care, or paid sick leave.

Furthermore, undocumented workers--many of whom are working in vulnerable sectors, such as food supply and retailing--are at a greater risk because they have no access to employment benefits or paid sick leave. In addition, undocumented communities have minimal access to federal support because federal COVID-19 aid was only made available to those with a social security number and those who had paid federal income taxes.

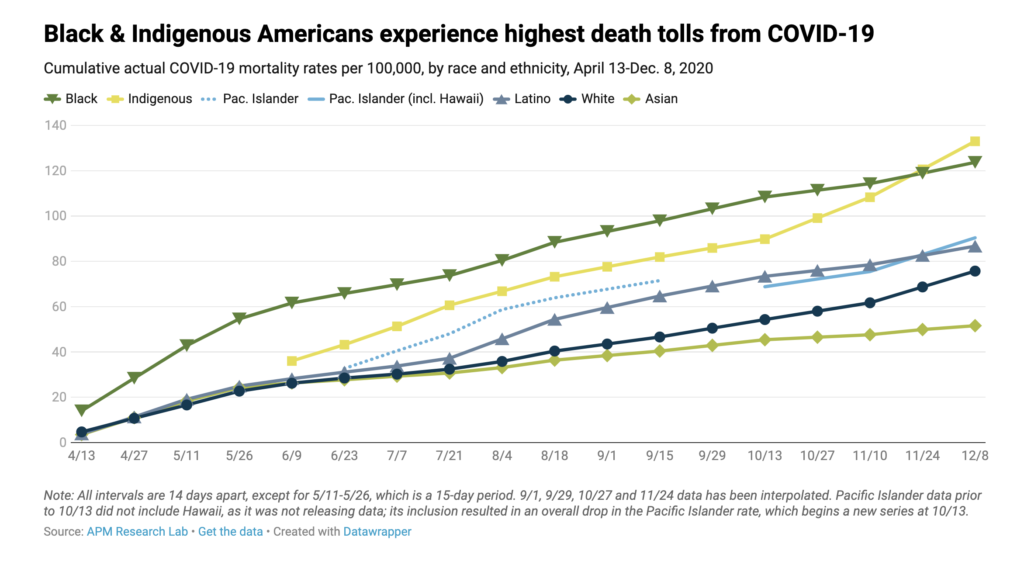

As more states release demographic data on COVID-19 cases and mortalities, it has become clear that the virus is impacting the most marginalized and vulnerable populations the hardest.

When adjusting the data for age differences in race and ethnicity groups, Black, Indigenous, Pacific Islander, and Latinx Americans all have COVID-19 death rates of triple or more the rate of white Americans. Specifically, compared to white people, the 2020 U.S. age-adjusted COVID-19 mortality rate for:

- Black people is 3.6 times as high

- Indigenous people is 3.4 times as high

- Latinx people is 3.2 times as high

- Pacific Islanders is 3.0 times as high, and

- Asians is 1.3 times as high.

As APM Research Lab has reported, this indicates that many younger Americans in these racial and ethnic groups are dying of COVID-19--driving their mortality rates far above white Americans. However, in every age category, “Black people are dying from COVID at roughly the same rate as white people more than a decade older.” This data reveals the inequitable impacts of COVID-19 and highlights the racial disparities policymakers must address.

It is also important to note that not every state has published comprehensive demographic data on the racial, ethnic, and language characteristics for those affected by COVID-19. There are still many states where race and/or ethnicity is unknown for a significant share of not only confirmed cases and deaths, but also general testing results. Expanded testing has provided more insight into the spread of COVID-19 and its impacts on marginalized communities. However, there has been many barriers to equitable testing that prevent proper data collection. For example, drive-in testing sites often require a vehicle to be tested. But Black households and people of color are least likely to have access to a vehicle. Targeting testing resources, such as accessible sites, supplies, and tailored messaging, could alleviate ongoing and future health disparities due to the pandemic.

In addition, a lack of uniform reporting guidelines across the U.S, has made it difficult to estimate the pandemic’s true toll on different communities. For example, many states lump Hispanic and Latinx identities together in the racial breakdown, whereas other states do not. In addition, some lump Indigenous people into the “Other” category, preventing states from being able to identify the complete effects of the virus on the Indigenous community. Without extensive and accurate demographic data, policymakers and researchers have no way to address ongoing inequities and identify which populations need additional access to resources.

It is critical that state legislators account for existing racial disparities in health care access and take steps to promote health equity. Some state legislatures across the country are addressing racial and ethnic disparities by adopting policies that expand health coverage and promote racial data transparency. This report summarizes some of the most important state-level developments from 2020 legislative sessions.

Racial Data Transparency

State legislators are taking action to increase racial and health data transparency by:

- Advocating for better data collection and reporting of comprehensive racial data;

- Investing in contact tracing programs;

- Putting in place a racial impact component within legislation that may affect racial and ethnic groups;

Better Data Collection And Reporting Of Racial Data

Without comprehensive race and ethnicity data, the communities most impacted by

the pandemic cannot be identified. As a result, some lawmakers are pushing for a more comprehensive collection of frequently updated data not only related to COVID-19, but also for any future public health emergencies.

A. Comprehensive COVID-19-related Data Collection

Massachusetts passed a bill (MA HB 4672/Chapter 93), which requires the state’s department of public health to collect data from all boards of health and publicly report the daily total and complete aggregate numbers of those who have tested positive for COVID-19, have been hospitalized, and have died as a result of a confirmed or probable case. It also requires the department to publish a daily report on such data from each state and county correctional facility, and elder care facilities. Each daily report must allow for the identification of trends, testing, infection, hospitalization, and mortality based on demographic factors, including race and ethnicity.

New Jersey enacted legislation (NJ S 2357/Chapter 28), which requires hospitals to report to the state’s department of health demographic data, including race and ethnicity, on not only confirmed COVID-19 cases and deaths, but also the number of those who are admitted for treatment, those who attempt to get treated, and those who are turned away after attempting to get tested. The data will be posted publicly, updated on a daily basis, and compiled by county and municipality. Michigan also introduced a similar bill (MI HB 5753), but it failed to pass.

New York legislators introduced a bill (NY SB 8360) that did not include as many components as Michigan’s or New Jersey’s, but would have uniquely required data related to all COVID-19 testing regardless of the result, including the number of individuals tested. In addition, the bill would have required reporting of not only general demographic information, like race and ethnicity, but also primary language, socioeconomic status or occupation, disability status, and county or city of residence. Massachusetts enacted legislation (MA HB 4672/Chapter 93) with a similar component.

In Michigan, a bill (MI HB 5753) introduced in the House would have required hospitals to collect and report to the state’s department of health comprehensive demographic data on those affected by COVID-19 or any other communicable disease and infection during a future state of emergency. Louisiana enacted a resolution (LA SR 76) with similar language.

New York legislators introduced legislation (NY SB 8360), which included a component that would have required the Department of Health to submit to specific legislative committees a preliminary report on the following: (1) description of COVID-19-associated race and ethnicity data, and (2) evidence-based response strategies for future pandemics.

Investment In Contact Tracing Programs

Contact tracing sheds light on how a disease, such as COVID-19, is spread by locating, talking, and working with people who have tested positive for the virus to identify and track people with whom they have been in close contact. Because the United States did not have a national contact tracing strategy, there has been insufficient data about how different populations are being affected by the virus. Thus, states are investing in contact tracing programs to collect more comprehensive data that accurately reflects the impacts of COVID-19 on different communities.

A. Allocation of Funds for Contact Tracing Programs

State lawmakers have worked to appropriate funds from either the CARES Act’s Coronavirus Relief Fund or their general fund for the purpose of expanding public and private initiatives for COVID-19 testing, contact tracing, and trends tracking and analysis. These funds could be used to hire contact tracers, purchase necessary equipment, and expand the contact tracing infrastructure to take appropriate public health actions. Hawaii’s legislature enacted this legislation (HI SB 75), while similar bills were introduced but failed in Minnesota (MN HF 4579) and North Carolina (NC HB 1038).

South Carolina passed a bill (SC HB 3411) that requires the Medical University of South Carolina, in consultation with other health departments and associations, to develop and deploy a statewide COVID-19 testing plan. To implement the plan, the Department of Health and Environmental Control will collaborate with hospitals and other medical stakeholders, and provide access to information on hotspots and contact tracing. The plan also emphasizes testing in rural communities and communities with a high prevalence of COVID-19 and/or with demographic characteristics consistent with risk factors for COVID-19.

B. Contact Tracing Representation

New York enacted legislation (NY AB 10447), which requires city contract tracers to be representative of the cultural and linguistic diversity of the communities they will serve. In addition, it mandates New York City’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene and the city’s health and hospitals corporations to submit an annual report on contact tracer worker diversity.

Similarly, South Carolina passed a bill (SC HB 3411), which mandates the Department of Health to identify no fewer than 1,000 contact tracers who are best suited to interact in a culturally appropriate manner and in the required languages of those disproportionately affected by COVID-19.

C. Privacy Protections

While contact tracing programs are crucial for collecting COVID-19 data and increasing racial data transparency, these programs have privacy implications that can harm immigrant communities and other marginalized groups. There have been concerns about whether or not confidential information would be misused or shared to other government agencies, such as immigration authorities and law enforcement, for reasons unrelated to the goal of tracking the spread of the virus. For example, police in Minnesota have reportedly used contact tracing data to track protestors from racial justice demonstrations. Allowing law and immigration enforcement to access and weaponize contact tracing data would disproportionately harm communities of color who are already being hit the hardest by the pandemic.

To protect these communities and encourage participation in contact tracing programs, legislators must prohibit immigration authorities and law enforcement from accessing contact tracing data. New York legislators enacted legislation (NY AB 10500/Chapter 377) that protects the data compiled by contact tracers from legal processes. In addition, it specifies that no contact tracer or contact tracing entity may provide contact tracing information to a law enforcement entity or immigration authority.

Kansas passed a similar bill (KS HB 2016/Section 16), which requires contact tracing data to be used only for the purposes of contact tracing. The data must be confidential and not disclosed, and safely and securely destroyed when no longer necessary for contact tracing. The bill also prohibits the state or any municipality, or any officer or official or agent thereof, from conducting or authorizing contact tracing, except under certain circumstances.

Racial Impact Statements Within Legislation

State lawmakers are trying to address racial disparities through the inclusion of racial impact statements in legislation. Similar to the fiscal notes often attached to legislation, a racial impact statement would analyze and address how different racial and ethnic groups will be negatively or positively impacted by proposed legislation. The analysis is used to not only inform legislators’ decisions, but also reduce, eliminate, and prevent racial discrimination and inequities. Illinois legislators introduced a bill (IL HB 4428), which would have required a racial impact statement for any legislation that has or could have a disparate impact on racial and ethnic groups.

Massachusetts and Ohio introduced a more specific set of legislation (MA HD 2789/SD 936 and OH HB 620) that would have required a racial impact and health disparities analysis for health-related initiatives and policies. Ohio’s legislation took a more progressive lead by also requiring the statements to determine whether introduced bills have a positive, negative, or neutral impact on the accomplishment of health equity in the state, health or health equity of specific populations in geographic areas, and the social determinants of health for the most vulnerable populations.

Addressing Disparities In COVID-19 Treatment And Testing

Lawmakers are seeking to address disparities by making healthcare more accessible to vulnerable communities through the expansion of telehealth, Medicaid, and insurance coverage.

Telehealth

In order to prevent the spread of COVID-19, many health care systems have begun utilizing telehealth and telemedicine technology for medical appointments. Such reliance on technology creates barriers for those who lack access to quality broadband and telephone services.

State legislators are expanding access to healthcare by:

- Ensuring telehealth payment parity;

- Expanding telehealth coverage for audio-only appointments; and

- Waiving or lowering cost-sharing for telehealth and telemedicine.

A. Ensuring telehealth payment parity

In order to mitigate the spread of COVID-19, healthcare systems have had to adopt methods, such as telehealth, that do not rely on delivering health care services in-person. In response, state legislators have introduced payment parity bills that would require insurance plans to provide a reimbursement rate for telehealth services that is equal to, on the same basis as, or no less than the rate provided for in-person services.

Vermont enacted legislation (VT HB 742/Section 24), which includes a component on payment parity. In addition, the following states all introduced variations of this type of bill, but none were enacted:

- Illinois (IL HB 4963 and IL SB 2561)

- Iowa (IA HF 2192)

- Michigan (MI SB 898)

- New Hampshire (NH SB 555)

- New Jersey (NJ SB 2559/A 4179)

- North Carolina (NC HB 1037/Section 6.2a)

- Rhode Island (RI SB 2525/Section 3)

A similar bill introduced in Washington (WA HB 2770) that would have allowed hospitals, hospital systems, telemedicine companies, and provider groups with 11 or more providers to negotiate their rate.

B. Expanding telehealth coverage for audio-only appointments

For telehealth services, some states require a provider and patient to use real-time, interactive audio and visual communication. However, such a requirement leaves patients who only have landline or audio-only phones without access to telehealth. Many of these patients are often low-income and come from marginalized communities. State lawmakers are working to increase access to healthcare for all by permitting audio-only telehealth appointments. Some have also restricted benefit and insurance plans from placing any restrictions on the electronic or technological platform used to provide these virtual services.

Colorado’s legislature enacted a bill (CO SB 20-212/Section 2) on this topic, while variations of this legislation are pending in New Jersey (NJ SB 2559/A 4179) and failed in Rhode Island (RI SB 2525/Section 3).

New Jersey legislators also enacted a different bill (NJ AB 3860/SB 2289), which waives certain regulatory requirements in order to facilitate telemedicine health services during COVID-19, including any privacy requirements that would limit the use of technological devices that are not typically used in telehealth services.

C. Waiving or lowering cost sharing for telehealth and telemedicine

State lawmakers are eliminating barriers to telehealth by waiving or lowering cost-sharing for telehealth services related to COVID-19.

New Jersey enacted a bill (NJ AB 3843), which provides coverage for telemedicine and telehealth to the same extent for any other services, except that no cost-sharing shall be imposed on the coverage.

Michigan introduced legislation (MI HB 5633) which would have required examination, diagnosis, and prescribed treatment of COVID-19 by telemedicine to not be subject to any coinsurance, copayment, application to a deductible, or limit.

Medicaid And Insurance Coverage

State legislators are working to address health inequities by proposing legislation that would:

- Move more states to adopt the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion;

- Expand Medicaid and insurance coverage for uninsured, undocumented, and low-income individuals; and

- Waive or lower cost-sharing for COVID-19 testing and treatment.

A. Expanding Medicaid in states without Medicaid expansion

Thirty-eight states, and D.C., have expanded their Medicaid program under the Affordable Care Act.

Of the 38 states, Oklahoma and Missouri passed expansion initiatives (OK State Question 802 and MO Amendment 2) that will be implemented in 2021. That leaves nearly two million people in 12 states who are ineligible for Medicaid coverage and left without access to an affordable coverage option. The COVID-19 emergency is putting intense pressure on these states to ensure greater access to quality health care for all, especially those disproportionately impacted by the pandemic. As a result, some lawmakers in these 12 states have sought to expand the eligibility requirements for their Medicaid programs.

North Carolina (NC HB 1040), South Carolina (SC HB 5476), Alabama (AL HB 447), Kansas (KS SB 252), and Florida (FL SJR 224/HJR 247) introduced bills to adopt the ACA’s Medicaid Expansion, which provides Medicaid coverage to non-elderly adults with incomes below 138 percent of the poverty line (though none of these bills passed).

North Carolina also introduced a different bill (NC HB 1038/Section 3A) that would have provided temporary, targeted Medicaid coverage to individuals with incomes up to 200%, rather than 133%, of the poverty line for COVID-related services. In addition, it would have provided Medicaid coverage for COVID-19 testing to the uninsured.

B. Expanding Medicaid and insurance coverage for uninsured individuals, low-income groups, and undocumented communities during the pandemic.

State legislators are working to address COVID-19-related health disparities by expanding insurance coverage for uninsured, low-income, and undocumented communities.

Ohio introduced legislation (OH HB 583) that would have temporarily waived certain Medicaid requirements during the pandemic and expand financial eligibility to 300% of the poverty line for children and 200% for adults. In addition, the state introduced a resolution (OH HCR 27) which demanded the Trump Administration to create a special enrollment period in the ACA marketplaces for uninsured Ohioans who may be unable to access COVID-19 testing and treatment.

Minnesota enacted an exhaustive COVID-19-related legislation (MN HF 4556/Section 11), which included a provision for Medicaid to cover the COVID-19 testing of uninsured individuals. Similarly, New York also introduced a bill (NY SB 8123/AB10494) that would have allowed any uninsured individual, regardless of immigration status, be eligible for COVID-19 testing at no cost.

Legislation in New York (NY SB 8366) would have amended the state’s social services law and increase COVID-19 health services eligibility for those who are residents of the state, have a confirmed case of COVID-19, have a household income below 200% of the FPL, and are ineligible for federal financial participation in the basic health program on the basis of immigration status.

C. Waiving or lowering cost-sharing for COVID-19 testing and treatment

Increased access to the COVID-19 testing and treatment will enable local and state public health departments to accurately track the course of the pandemic. It is also critical that people receive affordable and equitable access to health care services, especially during this time. State lawmakers are focusing on ensuring health care affordability and accessibility for those impacted by the virus by waiving or lowering cost-sharing for COVID-19-related services. These services may include, but are not limited to, diagnostic and antibody testing, physician office visits, telemedicine services, hospitalizations, antiviral drugs, and vaccines.

Louisiana and New Jersey enacted similar laws (LA SB 426 and NJ AB 3843), while variations on this type of legislation were introduced but failed to pass in Minnesota (MN HF 4416), Michigan (MI HB 5633), and Ohio (OH HB 579).

Complementary Policies

- Create a Commission to study COVID-19 racial disparities and recommend actions to policymakers, community leaders, and healthcare systems that promote health equity and address the factors that leave racial, ethnic, and indigenous communities vulnerable during public health emergencies.

- Increase broadband access and close the digital divide to ensure communities have access to the communication tools necessary for accessing medical care through telehealth and telemedicine appointments.

- Increase pay and protections for frontline workers, and ensure these workers have access to paid sick leave. Paid sick leave allows employees to take care of themselves and/or their loved ones during the pandemic without having to sacrifice their financial and job security.

- Allocate resources to communities most impacted by COVID-19 by setting up testing centers in low-income areas and within existing community networks, such as community health centers and organizations. These sites will help expand access to COVID-19 testing for those who have had limited access before.

Additional Resources

General Information

- 3 Principles for an Antiracist, Equitable State Response to COVID-19—and a Stronger Recovery, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

- Race Equity in State and Local COVID-19 Responses Checklist, Community Catalyst

- State Options to Provide COVID-19 Testing, Treatment, and Vaccination for Uninsured Immigrants, Community Catalyst

- State Data and Policy Actions to Address Coronavirus, Kaiser Family Foundation

- COVID-19 & Race: Principles, PolicyLink

- Reducing Health Disparities Through a Focus on Communities, PolicyLink

Racial Data Transparency & Contact Tracing

- The COVID Racial Data Tracker, The COVID Tracking Project

- Counting a Diverse Nation: Disaggregating Data on Race and Ethnicity to Advance a Culture of Health, PolicyLink

- State of COVID-19 Contact Tracing in the U.S., United States of Care

- How States Collect Data, Report, and Act on COVID-19 Racial and Ethnic Disparities, National Academy for State Health Policy

- Advances in States’ Reporting of COVID-19 Health Equity Data, State Health and Value Strategies

Health & Equity Policy

- State and Federal Telehealth Legislation and Regulation Tracking, Center for Connected Health Policy

- U.S. States and Territories Modifying Requirements for Telehealth in Response to COVID-19, Federation of State Medical Boards

- Advancing Health Equity through Telehealth Interventions during COVID-19 and Beyond: Policy Recommendations and Promising State Models, Families USA

- The Fierce Urgency of Now: Federal and State Policy Recommendations to Address Health Inequities in the Era of COVID-19, Families USA

- Medicaid Emergency Authority Tracker, Kaiser Family Foundation

- Racial Equity Resources on Health and Healthcare, Racial Equity Tools